It is essential to know the meaning of firm and industry before analyzing the two. Firm is an organization which produces and supplies goods that are demanded by the people with the goal of maximizing its profits.

According to R.L.Miller, “Firm is an organization that buys and hires resources and sells goods and services.” To Lipsey, “Firm is the unit that employs factors of production to produce commodities that it sells to other firms, to households, or to the government.”

Industry is a group of firms producing homogeneous products in a market. According to Lipsey, “Industry is a group of firms that sells a well-defined product or closely related set of products.” For example, Raymond, Maffatlal, Arvind, etc., are cloth manufacturing firms, whereas a group of such firms is called the textile industry.

Conditions of Equilibrium of the Firm and Industry

A firm is in equilibrium when it has no tendency to change its level of output. It needs neither expansion nor contraction. It wants to earn maximum profits in by equating its marginal cost with its marginal revenue, i.e. MC = MR.

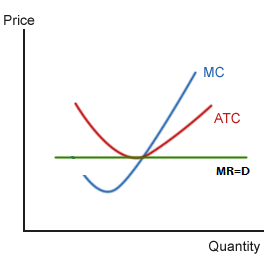

Diagrammatically, the conditions of equilibrium of the firm are:

(1) The MC curve must equal the MR curve. This is the first order and necessary condition. But this is not a sufficient condition which may be fulfilled yet the firm may not be in equilibrium.

(2) The MC curve must cut the MR curve from below and after the point of equilibrium it must be above the MR. This is the second order condition.’ Under conditions of perfect competition, the MR curve of a firm coincides with the AR curve. The MR curve is horizontal to the X- axis. Therefore, the firm is in equilibrium when MC=MR=AR (Price).

In Figure 1(A), the MC curve cuts the MR curve first at point A. It satisfies the condition of MC = MR, but it is not a point of maximum profits because after point A, the MC curve is below the MR curve. It does not pay the firm to produce the minimum output OM when it can earn larger profits by producing beyond OM.

Point В is of maximum profits where both the conditions are satisfied. Between points A and B. it pays the firm to expand its output because it’s MR > MC. It will, however, stop further production when it reaches the OM1 level of output where the firm satisfies both the conditions of equilibrium.

If it has any plans to produce more than OM1 it will be incurring losses, for its marginal cost exceeds its marginal revenue beyond the equilibrium point B. The same conclusions hold good in the case of a straight line MC curve as shown in Figure 1. (B)

An industry is in equilibrium: firstly when there is no tendency for the firms either to leave or enter the industry, and secondly, when each firm is also in equilibrium. The first condition implies that the average cost curves coincide with the average revenue curves of all the firms in the industry. They are earning only normal profits, which are supposed to be included in the average cost curves of the firms.

The second condition implies the equality of MC and MR. Under a perfectly competitive industry these two conditions must be satisfied at the point of equilibrium, i.e.

MC = MR … (1)

AC = AR … (2)

AR = MR

MC = AC = AR

Such a situation represents full equilibrium of the industry.

Short-Run Equilibrium of the Firm and Industry

SHORT-RUN EQUILIBRIUM OF THE FIRM

A firm is in equilibrium in the short-run when it has no tendency to expand or contract its output and wants to earn maximum profit or to incur minimum losses. The short-run is a period of time in which the firm can vary its output by changing the variable factors of production. The number of firms in the industry is fixed because neither the existing firms can leave nor new firms can enter it.

Assumptions:

This analysis is based on the following assumptions

- All firms use homogeneous factors of production.

- Firms are of different efficiency.

- Cost curves of firms vary from each other.

- All firms sell their products at the same price determined by demand and supply of the industry so that the price of each firm, P (Price) = AR = MR.

- Firms produce and sell different quantities.

The short-run equilibrium of the firm can be explained with the help of marginal analysis and total cost- total revenue analysis.

- Marginal Cost-Marginal Revenue Analysis

During the short run, a firm will produce only if its price equals the average variable cost or is higher than the average variable cost (AVC). Further, if the price is more than the averages total costs (SAC or АТС), i.e., P— AR > SAC, the firm will be earning supernormal (or abnormal) profits.

If price equals the average total costs, i.e., P = AR = SAC, the firm will be earning normal (or zero) profits or breaks-even. If price equals AVC, the firm will be incurring a loss. If price falls even a little below AVC, the firm will shut down because in order to produce it must cover at least its AVC during the short-run.

So during the short-run under perfect competition, a firm is in equilibrium in all the above noted situations. We illustrate them diagrammatically as under.

(a) Supernormal Profits

The firm will be earning supernormal profits in the short-run when price is higher than the short-run average cost, as shown in Figure 2 (A). The firm is in equilibrium at point E1 where SMC=MR and SMC cuts MR from below. OQ, is the equilibrium output and OP (=Q1E1) is the equilibrium price. Q1S are the short-run average costs.

SE1 (=Q1E1-Q1S) is the profit per unit. TS (equilibrium output) (per unit profit) = TSE1P area is the supernormal profits.

(b) Normal Profits

The firm may earn normal profits when price equals the short-run average costs as shown in Figure 2 (B). The firm is in equilibrium at point E2 where SMC =MR and SMC cuts MR from below. OQ2 is the equilibrium output and OP (=Q2E) is the equilibrium price. The firm is earning normal profits because Price = AR = MR =SMC= SAC at its minimum point E2.

(c) Minimum Loss

The firm may be in equilibrium and yet incur a loss when price is less than the short-run average costs, as shown in Figure 2 (C). The firm is in equilibrium at point E3 where SMC = MR and SMC cuts MR from below. OQ3 is the equilibrium output and OP (=Q3E3) is the equilibrium price.

Since the average costs Q3B are higher than the price Q3E3, E3B is the loss per unit (Q3B-Q3E3). The total loss is PE3 x E3B = PE3BA. The firm will continue to produce OQ3 output so long as it is covering its average variable cost plus some of its fixed cost.

(d) Maximum Loss

If the price fig. 2 falls to the level of AVC, the firm will just cover its average variable cost, as shown in figure 2 (D). It is indifferent whether to operate or close down because its losses are the maximum.

It will pay such a firm to continue producing OQ4 output and incur PE4GF losses rather than close down in the short-run. OQ4 is the shutdown output because if the price falls below OP, the firm will stop production. E4 is, therefore, the shutdown point.

(e) Shut Down Stage

Figure 2. (E) shows a firm which is unable to cover even its AVC at OQ0 level of output because the price OP is below the AVC curve. It must shut down.

Thus in the short-run, there are firms which earn normal profits, supernormal profits and incur losses.

- Total Cost-Total Revenue Analysis

The short-run equilibrium of the firm can also he shown with the help of total cost and total revenue curves. The firm is able to maximize its profits when the positive difference between TR and TC is the greatest. This is shown in Figure 3 where TR is the total revenue curve and TC the total cost curve.

The total revenue curve is an upward sloping straight line curve starting from O. This is because the firm sells small or large quantities of its product at a constant price under perfect competition. If the firm produces nothing, total revenue will be zero the more it produces, the larger is the increase in total revenue. Hence the TR curve is linear and slopes upward.

The firm will maximize its profits at that level of output where the gap between the TR curve and the TC curve is the maximum. Geometrically, it is that level at which the slope of a tangent drawn to the total cost curve equals the slope of the total revenue curve. In Figure 3, the maximum amount of profit is measured by TP at OQ output.

At outputs smaller or larger than OQ between A and B points, the firm’s profits shrink. If the firm produces OQ1 output, its losses are the maximum because the TC curve is above the TR curve. At Q1 its profits are zero.

This is the break-even point of the firm. It starts earning profits when it produces beyond OQ1 output level. At OQ2 level, its profits are again zero. If it produces beyond this level, it incurs losses because TC > TR.

SHORT-RUN EQUILIBRIUM OF THE INDUSTRY

An industry is in equilibrium in the short-run when its total output remains steady, there being no tendency to expand or contract its output. If all firms are in equilibrium, the industry is also in equilibrium. For full equilibrium of the industry in the short-run, all firms must be earning only normal profits.

The condition for this is SMC = MR = AR = SAC. But full equilibrium of the industry is by sheer accident because in the short- run some firms may he earning supernormal profits and some incurring losses. Even then, the industry is in short-run equilibrium when its quantity demanded and quantities supplied are equal at the price which clears the market.

This is illustrated in Figure 4 where in Panel (A), the industry is in equilibrium at point E where its demand curve D and supply curve S intersect which determine OP price at which its total output OQ is cleared. But at the prevailing price OP, some firms are earning supernormal profits PE1ST, as shown in Panel (B), while some other firms are incurring FGE2P losses, as shown in Panel (C) of the figure.

Long-Run Equilibrium of the Firm and Industry

LONG-RUN EQUILIBRIUM OF THE FIRM

The long run is a period of time in which the firm can change its plant and scale of operations. Thus in the long-run all costs are variable and there are no fixed costs. The firm is in the long-run equilibrium under perfect competition when it does not want to change its equilibrium output.

It is earning normal profits. If some firms are earning supernormal profits, new firms will enter the industry and supernormal profits will be competed away. If some firms are incurring losses, some of the firms will leave the industry till all earn normal profits.

Thus there is no tendency for firms to enter or leave the industry because every firm must earn normal profits. “In the long-run, firms are in equilibrium when they have adjusted their plant so as to produce at the minimum point of their long-run AC curve, which is tangent (at this point) to the demand (AR) curve defined by the market price” so that they earn normal profits.

Assumptions

This analysis is based on the following assumptions

- Firms are free to enter into or leave the industry.

- All firms are of equal efficiency.

- All factors are homogenous. They can be obtained at constant and uniform prices. SMC

- Cost curves of firms are uniform.

- The plants of firms are equal, having given technology.

- All firms have perfect knowledge about price and output.

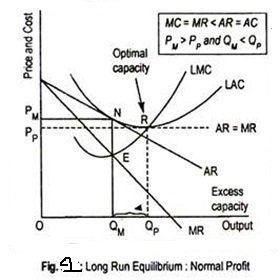

Given these assumptions, each firm of the industry will be in long-run equilibrium when it fulfils the following two conditions.

(1) In equilibrium, its short-run marginal cost (SMC) must equal to its long-run marginal cost (LMC) as well as its short-run average cost (SAC) and its long-run average cost (LAC) and both should equal MR=AR=P.

Thus the first equilibrium condition is

SMC = LMC = MR = AR = P = SAC = LAC at its minimum point, and

(2) LMC curve must cut MR curve from below: Both these conditions of equilibrium are satisfied at point E in Figure 5 where SMC and LMC curves cut from below SAC and LAC curves at their minimum point E and SMC and LMC curves cut AR = MR curve from below. All curves meet at this point E and the firm produces OQ optimum output and sells it at OP price.

Since we assume equal costs of all the firms of industry, all firms will be in equilibrium in the long-run. At OP price a firm will have neither a tendency to neither leave nor enter the industry and all firms will earn normal profits.

LONG-RUN EQUILIBRIUM OF THE INDUSTRY

The industry is in equilibrium in the long-run when all firms earn normal profits. There is no incentive for firms to leave the industry or for new firms to enter it. With all factors homogeneous and given their prices and the same technology, each firm and industry as a whole are in full equilibrium where LMC = MR = AR (-P) = LAC at its minimum.

Such an equilibrium position is attained when the long-run price for the industry is determined by the equality of total demand and supply of the industry.

The long-run equilibrium of the industry is illustrated in Figure 6 (A) where the long-run price OP is determined by the intersection of the demand curve D and the supply curve S at point E and the industry is producing OM output. At this price OP, the firms are in equilibrium at point A in Panel (B) at OQ level of output where LMC = SMC = MR =P ( = AR) = SAC = LAC at its minimum.

At this level, the firms are earning normal profits and have no incentive to enter or leave the industry. It follows that when the industry is in long-run equilibrium, each firm in the industry is also in long-run equilibrium. If both the industry and the firms are in long-run equilibrium, they are also in short-run equilibrium.

Like this:

Like Loading...