According to the book “Discovering Psychology” by Don Hockenbury and Sandra E. Hockenbury, an emotion is a complex psychological state that involves three distinct components: a subjective experience, a physiological response, and a behavioral or expressive response.

In addition to trying to define what emotions are, researchers have also tried to identify and classify the different types of emotions. The descriptions and insights have changed over time:

- In 1972, psychologist Paul Eckman suggested that there are six basic emotions that are universal throughout human cultures: fear, disgust, anger, surprise, happiness, and sadness.

- In 1999, he expanded this list to include a number of other basic emotions, including embarrassment, excitement, contempt, shame, pride, satisfaction, and amusement.2

- In the 1980s, Robert Plutchik introduced another emotion classification system known as the “wheel of emotions.” This model demonstrated how different emotions can be combined or mixed together, much the way an artist mixes primary colors to create other colors.

Analysis of Emotions

(i) Fear

It is an emotion excited by the apprehension of a dangerous situation. McDougall holds that the emotion of fear is the affective aspect of instinct to escape. Fear is excited by a deafening noise, a blinding flash of lighting a sudden peal of thunder, etc. It arises from the perception of an object which caused pain or injury in the past.

The conditions which excite fear must be aggressive or obtrusive in their nature. A sudden and intense impression excites fear. A loud sound for which we are unprepared excited fear in us. Fear is expressed in quick palpitation of the heart, trembling, drooping of the limbs, running away etc. Extreme terror is expressed in immobility of the body.

(ii) Anger

It is an emotion excited by the thwarting of conation. It arises from obstruction of any instinctive or acquired tendency. McDougall holds that the emotion of anger is the affective aspect of the instinct of combat.

Any kind of opposition, or thwarting of an instinctive or acquired tendency, may cause anger. A cat becomes angry if you interfere with its kittens. A child becomes angry if you take away its toy. A. man becomes angry if you insult or abuse him.

The emotion of anger is the affective aspect of the instinct to fight to break down opposition. Anger and fear are characterized by opposite tendencies. In car, the bodily attitude is one of withdrawal, while in anger the body assumes an aggressive attitude.

Anger is expressed in a violent motor discharge. It is expressed in frowning, howling, grinding the teeth, closing the fists, kicking, striking, etc. Fear is expressed in trembling running away, etc.

(iii) Joy

It arises from the attainment of a cherished object. When the object of desire is attained, it gives rise to joy. It is expressed in a general heightened tension of the entire body. Erect posture, throwing out the chest, brightness of the eyes, smiling face, shooting, laughing, jumping, etc., are the expressions of joy.

(iv) Sorrow

It arises from the loss of a cherished object. It is excited by the failure to fulfil our desires. When a person is deprived of his cherished objects, he feels sorrow. Joy is the emotion that results from success of an endeavour, while sorrow is the emotion that results from impending or actual failure.

The expressions of sorrow are the opposite of those of joy. Drooping posture, retracting the chest, general relaxation of the bodily tension, etc., are the expressions of sorrow. Deep grief has a prostrating effect.

(v) Love

The word ‘love’ is ambiguous. It is used in three senses. First, it means sexual emotion. It is the emotion arising from the sex instinct. McDougall calls it the emotion of lust. Secondly, it means tender emotion arising from the maternal instinct.

Thirdly, it means a sentiment or permanent emotional disposition which is manifested in tender emotion. Selfish love seeks to satisfy itself, regardless of the welfare of the loved object. But, when it is excited, not merely by the presence of the loved object, but also by considerations for the welfare of the object it true emotion of love.

Love contains two elements, viz., attachment and sympathy. Attachment consists in fondling or caressing. Sympathy consists in sharing or entering into the emotions of others. Sully regards attachment or selfish love as the egoistic element and sympathy, as the altruistic element, in love.

Bain holds that attachment is a tender emotion which is expressed in bodily contact of some sort-touching, caressing, embracing, etc. In fact, the natural outlet of love, in all its forms, is delight in the society of, or in the presence of, the loved object.

(vi) Hate

The word ‘hate’ is ambiguous. It is used in the sense of a sentiment and an emotion both. According to McDougall, hate is a compound emotion. It consist of anger, fear, and disgust. The object of hatred provokes us, frightens us, and repels us. A powerful person who insults me excites anger in me. But anger cannot be expressed in fighting him. He is too powerful for me.

So he excites fear in me. This important anger mingled with fear is further complicated by disgust or loathing for the person. Hate is the opposite of love. It makes a person withdraw from the presence of the object of hate. While love is an expanding emotion, hate is a contracting emotion. It makes a person guard himself from others and withdraw from them. It is a defensive emotion.

Factors of Emotions

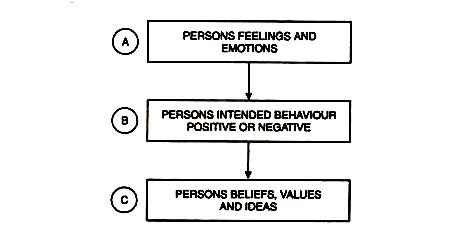

Every emotion has two sides bodily and mental. Mellone mentions the following factors in emotion:

(i) On the Mental Side

- The perception, memory, imagination or thought, of a situation which affects the material, mental, social or higher interests of the individual

- An affective quality tending towards pleasure or towards pain

- A tendency to activity

- A complication of organic sensations and muscular sensations.

(ii) On the Bodily Side

- Diffused changes in the internal organs

- Muscular movements

Theories of Emotions

- James-Lange Theory of Emotions

The common view is that an emotion arises from the perception, memory, or imagination, of a situation, and is expressed in organic changes. Thus, according to the common view, first there is perception, ideation, or thought; of a situation; than an emotion arises out of it; and then the emotion is expressed in organic changes.

Thus, emotion is prior to organic expression. You perceive a tiger at large; it excites fear in your mind, the emotion of fear gives rise to trembling and running away.

William James propounds just an opposite view. According to him, the perception of an object produces directly in reflex way organic changes in the internal organs; and these are reported to the brain by the sensory nerves and produce organic sensations. These organic sensations together with the perception of the object are called an emotion.

At first, there is a cold or feeling-less perception of a certain object, which is at once followed automatically by certain bodily or organic changes by a pre-organized mechanism, and then when these organic “reverberations” are reported back to the brain, the conscious correlates of these organic changes together with the original perception constitute an emotion.

Emotion, according to James, is a group of reflexly excited organic sensations clustered about the perception of an object. There is no element of feeling in an emotion. It is a mass of reflexly aroused organic sensations.

- Cannon’s Emergency Theory of Emotion

According to Cannon, the sympathetic system operates in a physical emergency to strengthen the organism for combat or any other unusual exertion. The perception of a complex situation quickens the action of the heart.

Accelerated heart action drives the blood more rapidly through the blood vessels, and thus washes away the products of fatigue more quickly. Further, the blood is diverted from the stomach and the intestines, so that the digestive processes are inhibited, and the skeletal muscles are better supplied with blood.

The liver discharges more sugar, which gives greater strength. The adrenal gland secretes adrenin, which stimulates the heart, increases blood-pressure, and tones up the fatigued muscles. Cannon tries to account for the changes in the internal organs, ductless glands and muscles accompanying emotions.

But a theory of the emotion derived from such nicely coordinated physiological activity appears to conflict with the fact that emotion is a diffuse and disruptive response. If an emotion were to emerge only in an ’emergency’, the individual would be thwarted very much in the normal course of his activity, since an emotion would occur only in a emergency.

An emergency is an unusual situation which calls for unusual exertion. It requires a new coordination involving complex bodily changes to meet the emergency. If greater physical strength, and endurance are required, the result may be successful.

But if a delicate coordination to obtain the desired end is required, the overwhelming responses produced by the activity of the autonomic nervous system may not achieve the end. The bodily changes produced by the autonomic nervous system may be effective in overcoming or escaping an assailant, but they are ineffective in mending a watch or planning an experiment.

- McDougall’s Theory of Emotion

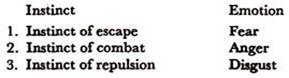

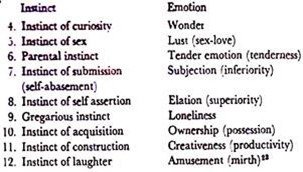

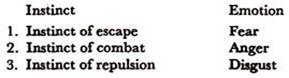

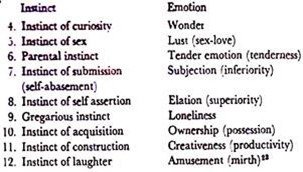

McDougall holds that emotions are functions of instincts. Primary emotions are conscious correlates of instincts. He says: “Each of the principal instincts conditions some one kind of emotional excitement whose quality is specific or peculiar to it”.

He gives the following pairs of instincts and emotions correlated to each other:

McDougall is right when he enunctates the principle that every emotive situation appeals to an instinctive tendency. But his list based on this principle is unscientific. For example, anger does not always arise from pugnacity; tender emotion may arise from other instincts than the parental.

McDougall mentions a number of instincts with less well-defined emotive reactions, e.g., the instinct of reproduction, the gregarious instinct, the instincts of acquisition and construction. Yet there are well-defined emotions of security, of self-expansion, of possession, etc., which have not been mentioned by McDougall.

His theory is very attractive, but it has not been worked out very satisfactorily. Some instincts (e.g., the instincts of walking, sitting, standing, running, etc.,) seem to have no specific emotions attached to them. Anger and fear resemble each other very closely as organic states, though they differ as impulses.

The really distinct emotions are much fewer than the instincts. So McDougall’s theory may be regarded as a working hypothesis. When we find an emotion, we find also a tendency to action that leads to some end-result.

But though emotion and instinct are closely connected with each other, we cannot hold that corresponding to every instinct there is an emotion and corresponding to every emotion there is an instinct. There are many instincts which are not accompanied by any specific emotions.

Further, the same emotion may include a variety of instinct in its system. The instinct of concealment and flight both operate in the emotion of fear. Again, the same expression may be connected with different emotions. Just as the same emotion may be organized in different sentiments, so the same instinct may be organized in different emotions.

The instinct of flight may operate in birds in fear as well as anger. Moreover, when the instinctive act evoked by a situation runs smoothly, the individual does not feel an emotion. But when the individual cannot effectively cope with the situation and his instinctive response is thwarted, he feels an emotion.

Therefore, an instinctive act is not always accompanied by an emotion. Hence McDougall’s theory may be regarded as a working hypothesis. It contains core of truth in it; it points out an intimate connection between instinct and emotion.

-

Philips Bard’s Theory of Emotion

Cannon (1927), refuted the James-Lange theory of emotion by showing that experimental subjects experienced and reported emotions before all bodily sensations. Therefore, emotions were not preceded and constituted by bodily sensations.

Bard (1934) later removed the cortex and thalamus of some animals and left only the posterior part of the hypothalamus and found that they still showed rage. But when he removed the hypothalamus also, they failed to show the integrated rage pattern.

Thus he proved that the hypothalamus was necessary for the expression of rage. His experiments did not prove that either the thalamus or hypothalamus generated rage (or any other emotion) or did they prove that the cortex normally inhibited the thalamus.

Masserman showed that convincingly by some experiments. He stimulated the hypothalamus in some normal cats by means of bipolar electrodes and they showed the integrated rage pattern, e.g., hissing, spitting, and unsheathing of claws. But these expressions did not disturb their normal activity.

Both Bard and Masserman also obtained the flight reaction in fear in a similar way. Bard removed the cortex and thalamus in cats, who showed fight reaction in response to air-blast. Masserman stimulated the hypothalamus of intact cats and obtained flight reaction.

But fear pattern exhibited by them differed from that of normal animals. Instead of strenuous attempts at escape made by frightened animals, these cats had fits of aimless and hasty running.

-

Emotion of the Ludicrous: Theory of Laughter

We should observe at the outset, that the ludicrous is not identical with the laughable. Laughter may arise from different sources. It may be excited by purely physical stimuli such as tickling. It is of the nature of a reflex action. Laughter may be excited by automatic imitation. You smile at a child and the child will smile at you. The people laugh in a crowd by automatic imitation.

They sometimes do not know the reason why they laugh. Laughter may arise from sympathetic reproduction .of the feelings of others. Emotions have a contagious effect. They spread from one person to another. When others faugh in exuberance of joy, we catch the contagion and laugh.

Laughter may arise from the consciousness of our own superiority over others. When we defeat our powerful adversary, we laugh in excess of elation. Laughter may be excited by the contemplation of the ludicrous.

Thus, the ludicrous is not identical with the laughable. Whatever is ludicrous is laughable, but whatever is laughable is not ludicrous. Laughter has many other causes hand ludicrous objects. The comic, emotion or the emotion of the ludicrous has the following characteristics.

It is an emotion of pure joy or elation unmixed with pain. It has a social significance. It is excited by incongruity in a situation, which is determined by a social standard of propriety or impropriety. It is a disinterested emotion devoid of a utilitarian motive.

Laughter is peculiar to the human species. Man is the only animal that laughs. He does not learn to laugh. He is provided by Nature with the complex mechanism of laughter. The impulse to laugh is instinctive.

Types of Emotions

McDougall classifies emotions into three types:

- Primary emotions

- Secondary or blended emotions

- Derived emotions

- Primary emotions

Primary emotions are the elementary effective correlates of instincts. Fear, anger, disgust, tender emotion, distress, lust or sex-love, curiosity, amusement, etc., which arise from the instincts of escape, combat, repulsion, parental instinct, appeal, sex, curiosity, laughter, etc., are primary emotions. They do not presuppose other emotions.

- Secondary or blended emotions

Secondary or blended emotions are the combinations of two or more primary emotions. When two or more cooperating or conflicting instinctive impulses are evoked by a complex situation, a secondary or blended emotion is aroused.

It may not be a blend or coalescence of two or more primary emotions. It may arise from a complex situation which excites two or more cooperating or conflicting instinctive tendencies which generally arouse two or more primary emotions.

It is the immediate response to a complex situation. McDougall avers that his treatment of the secondary emotions is not guilty of the errors of J.S. Mill’s “mental chemistry”. When a child approaches a snake and recedes from it out of fear and curiosity, he feels a blended emotion. Scorn is a blend of anger and disgust. Or, it is a blend of anger, disgust and positive self-feeling or elation.

It is a binary compound or a tertiary compound. Admiration is a compound of wonder and negative self-feeling or self-abasement. Awe is a compound of wonder, self-abasement and fear. Pity is a compound of tender emotion and sympathy pain or distress.

Reproach is a compound of tender feeling and anger. Hate is a blend of anger, fear and disgust. Jealousy, shame, revenge, gratitude, reverence etc., are blended emotions.

- Derived emotions

Derived emotions are the complex feelings, which are neither primary emotions nor blended motions but which are related to desires. They do not arise from the instinctive impulses. Confidence, hope, anxiety, despondency, despairs, regret, remorse, sorrow, etc., are derivative emotions.

Confidence, hope, anxiety, despondency and despair are the prospective emotions or desire. When a team of mountaineers start on a journey to reach a peak, they have confidence due to the anticipation of success. Their confidence arises from a strong desire for success.

When a member of the party falls seriously ill for a certain period, their confidence is reduced to hope. When they are hindered by a series of avalanches and landslides, their hope degenerates into anxiety. When farther on their journey they encounter freezing temperature, and shortage of food, and when some are crippled by frostbite, their anxiety is converted into despondency.

Later when their progress is thwarted by foul weather, heavy snowfall, and blizard, their despondency turns into despair. These derived emotions are called by Shand “the prospective emotions or desire” because they are related to desire that looks forward to the future.

Regret, remorse, and sorry are derived emotions which are called “the retrospective emotions of desire,” because they are related to desire which looks backward to the past. Regret arises from the frustration of a desire in the past, and is attended with pain.

Regret becomes remorse when the frustration of a desire in the past was due to one’s misjudgement or negligence of duty. It is attended with self-reproach. Sorrow is tender regret arising from the loss of a cherished object. It is a painful emotion of retrospective desire. Derived emotions may arise from prospective or retrospective aversion also.

Primary emotions are based on instincts excited by a situation. Derived emotions are not directly based on instincts, but they presuppose some desire or aversion which operates when a situation is apprehended. Primary emotions are comparatively simple and elementary, while derived emotions are complex and presuppose some mental development and operation of prospective or retrospective desire or aversion.

Development of Emotions

Primary emotions are refined in three ways. First, they are refined by modifications of the motor response by which socially acceptable reactions are substituted for the primitive emotional expressions such as crying, kicking, scratching, biting, etc.

The emotional expressions of a cultured person are different from those of a child or a savage. Secondly, primary emotions are modified by new attachments on the side of the stimulus.

The primary emotion of fear is originally excited by the perception of a dangerous situation, e.g., the sight of a tiger at large. But later it is excited by the imagination or thought of a serious situation, e.g., the loss of a job, the imminent death of an earning member of a family, the fall of a Government, etc.

Thirdly, primary emotions are modified by a combination of one with another. Awe is a compound of wonder, fear and humility. Hate is a compound of anger, fear and disgust. Pity is a compound of grief and tenderness”.

The situations which excite specific emotions in older children and adults excite only general excitement in new born infants. Gradually distress, delight, fear, disgust, anger, affection and joy are differentiated from the general excitement in two years.

Maturation and learning both play important roles in the development of emotion. As the organism matures the infant exhibits such emotional responses as crying, weeping, smiling and laughing without earning them.

They appear almost at the same age in all children even when they are not allowed opportunities to imitate them from others. Facial expressions of deaf-blind children also confirm the influence of maturation in emotional development.

The stereotyped facial and gestural expressions which are peculiar to persons of a particular culture are learned from others. The clapping of hands is a sign of happiness in us, but of disappointment in the Chinese. The raising of the eyebrows and the opening of the eyes widely are expression of surprise in us, but the sticking out of tongues, in them. These peculiar expressions show the influence of learning and culture.

Emotions and their expressions are due to conditioning. A child of nine months exhibited fear reactions to a loud noise. When a rat was placed before him, he had no fear response. But when a rat was placed before him subsequently a number of times when a loud noise was produced on each occasion, the child showed fear reaction. Later when only a rat was placed before him, he exhibited fear reaction.

Thus his fear was conditioned by a substitute stimulus. Sometimes emotions are learned by imitation. If the parent is afraid of particular objects (e.g., darkness, lightning, snakes, etc.), the children get afraid of them. Obviously, their emotion is influenced by imitation.

Degrees of Emotional Responsiveness

Normal persons differ in their general emotional responsiveness. There are calm persons who are generally not perturbed, by emotions. There are excitable persons who are deeply stirred by emotions. These are two extremes. There are many degrees of emotionality between these two extremes.

- Emotional Excess

Some persons have an excess of emotionally. They are susceptible to all emotions. Their emotions are easily excited by slight stimuli. Joy, fear, anger, sorrow, and other emotions are easily and frequently aroused. They are usually intense. Joy becomes ecstasy, fear becomes terror, anger becomes violent rage, and sorrow becomes’ intense grief. Emotions are felt in their intensity.

- Emotionally Instability

Generally the persons who have an excess of emotionality have also emotional instability. They often shift abruptly from joy to sorrow, from love to hate; from self-confidence to diffidence. This is called emotional instability. It is generally accompanied by emotional sensitivity and excess of response.

But excessive emotionality and emotional instability do not invariably go together. Sometimes emotional instability is found along with nervous and mental instability.

- Unemotional Nature

The extremely unemotional individual is not dead to all emotions. But his emotions are not easily aroused. They are by no means unemotional. Unemotional persons do not experience difficulties in adapting themselves to the social environment. But over-emotional persons cannot easily adapt themselves to it.

In the emotional person the sympathetic nervous system is readily excited and brings about visceral changes. Excessive sensitivity of the sympathetic systems is the cause of excessive emotionality and emotional instability.

Like this:

Like Loading...