Internal Rate of Return, Advantages, Disadvantages, Calculation, Formula

The Internal Rate of Return (IRR) is the discount rate at which the Net Present Value (NPV) of a project becomes zero. It represents the expected annual return on an investment, helping businesses evaluate the profitability of potential projects. A higher IRR indicates a more attractive investment opportunity. IRR is widely used in capital budgeting decisions, comparing it with the cost of capital to determine project feasibility. However, IRR has limitations, such as multiple values for projects with non-conventional cash flows. Despite this, it remains a key tool for financial analysis and decision-making in corporate finance.

Advantages Of IRR:

-

Considers the Time Value of Money

IRR method takes into account the time value of money, ensuring that future cash flows are discounted appropriately. Unlike simple return calculations, IRR recognizes that a rupee today is worth more than a rupee in the future. This makes IRR a more accurate tool for evaluating long-term investment projects. By discounting cash flows, it provides a clearer picture of a project’s true profitability, making it easier for businesses to make informed financial decisions.

-

Provides a Clear Investment Decision Rule

IRR offers a straightforward decision-making rule: if the IRR is higher than the cost of capital, the project is considered financially viable. This simplifies comparisons between different investment opportunities. Businesses can easily determine whether a project will generate returns exceeding their required rate of return. This clear and intuitive approach helps managers and investors assess the attractiveness of various investment options without needing complex calculations.

-

Facilitates Easy Comparisons Between Projects

Since IRR expresses profitability as a percentage, it allows companies to compare multiple investment opportunities regardless of size. This makes IRR particularly useful when selecting projects with different initial investment amounts. By ranking projects based on IRR, businesses can prioritize those with the highest potential returns. This comparative approach simplifies capital allocation and ensures that resources are invested in the most profitable ventures.

-

Does Not Require a Predetermined Discount Rate

IRR is independent of external assumptions. This is beneficial because determining an accurate discount rate can be challenging. By calculating the inherent rate of return, IRR allows businesses to assess profitability without relying on uncertain external factors. This self-sufficiency makes IRR a flexible tool for evaluating investment decisions.

-

Works Well for Projects with Conventional Cash Flows

IRR is particularly effective for projects with standard cash flow patterns—an initial outflow followed by a series of inflows. In such cases, IRR provides a single, clear rate of return that accurately reflects the project’s profitability. This makes it a practical method for evaluating straightforward investments such as factory expansions, equipment purchases, and infrastructure developments.

-

Useful for Capital Rationing Decisions

When companies face budget constraints, IRR helps prioritize investments by ranking projects based on their profitability. Businesses with limited capital can select projects with the highest IRRs to maximize returns. This ensures that financial resources are allocated efficiently, improving overall investment performance. By considering both return potential and capital constraints, IRR serves as a valuable tool in strategic financial planning.

Disadvantages Of IRR:

-

Ignores the Scale of Investment

One major drawback of IRR is that it does not consider the size of the investment. A project with a high IRR may have a much smaller total return compared to a project with a lower IRR but a larger overall profit. This can mislead decision-makers into selecting smaller, high-IRR projects over larger, more profitable ones. The Net Present Value (NPV) method is often preferred because it accounts for the absolute value of profits rather than just the percentage return.

-

Assumes Cash Flow Reinvestment at IRR

IRR assumes that all future cash flows are reinvested at the same rate as the IRR itself. In reality, companies may not always be able to reinvest funds at such a high rate. This can lead to overestimating the actual profitability of the project. The Modified Internal Rate of Return (MIRR) is sometimes used to address this issue by assuming reinvestment at a more realistic rate, such as the cost of capital.

-

Multiple IRRs in Non-Conventional Cash Flows

Projects with unconventional cash flows—where cash inflows and outflows occur more than once—can result in multiple IRRs. This happens when a project has cash flow reversals, such as an outflow followed by an inflow, then another outflow. In such cases, the IRR formula produces more than one valid percentage, making it difficult to determine the actual rate of return. This creates confusion and reduces the reliability of IRR as a decision-making tool.

-

Fails to Consider the Cost of Capital

IRR does not explicitly take the cost of financing into account. A high IRR does not necessarily mean a project is profitable if the company’s cost of capital is also high. This limitation makes IRR less reliable for firms with fluctuating or high financing costs. Decision-makers must always compare IRR with the cost of capital to make sound investment choices.

-

Not Ideal for Mutually Exclusive Projects

When comparing mutually exclusive projects (where selecting one project eliminates the possibility of choosing another), IRR may lead to incorrect decisions. A project with a higher IRR but lower NPV might be chosen over a project with a lower IRR but significantly higher total value. Since NPV directly measures value addition, it is a better metric in such cases. Relying solely on IRR for mutually exclusive projects can result in suboptimal investment decisions.

-

Complexity in Calculation

Calculating IRR can be complicated, especially for projects with irregular cash flows. Unlike NPV, which uses a simple discounting formula, IRR requires iterative trial-and-error methods or financial software to determine the correct rate. This complexity can make it difficult for managers without strong financial expertise to interpret results. Additionally, IRR does not work well when projects have delayed or highly unpredictable cash flows.

Calculation Of IRR:

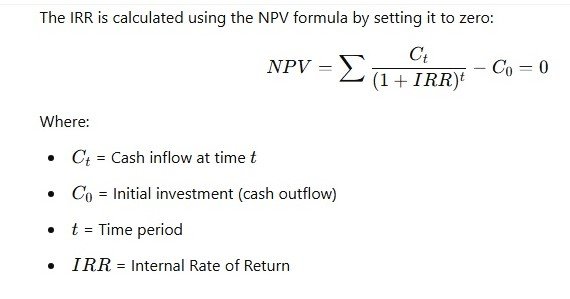

The Internal Rate of Return (IRR) is the discount rate that makes the Net Present Value (NPV) of a project equal to zero. It is the rate at which the present value of future cash inflows equals the present value of cash outflows.

Formula for IRR:

The IRR is calculated using the NPV formula by setting it to zero:

Decision Rules Of IRR:

If projects are independent

* Accept the project which has higher IRR than cost of capital(IRR> k).

* Reject the project which has lower IRR than cost of capital(IRR

If projects are mutually exclusive

* Accept the project which has higher IRR

* Reject other projects

For the acceptance of the project, IRR must be greater than cost of capital. Higher IRR is accepted among different alternatives.