Degrees of Price Discrimination

Price discrimination means charging different prices from different customers or for different units of the same product. In the words of Joan Robinson: “The act of selling the same article, produced under single control at different prices to different buyers is known as price discrimination.” Price discrimination is possible when the monopolist sells in different markets in such a way that it is not possible to transfer any unit of the commodity from the cheap market to the dearer market.

Degrees of price discrimination

Prof. Pigou in his Economics of Welfare describes three degrees of discriminating power which a monopolist may wield. The type of discrimination discussed above is called discrimination of the third degree. We explain below discrimination of the first degree and the second degree.

Discrimination of the First Degree (1st) or Perfect Discrimination

Discrimination of the first degree occurs when a monopolist charges “a different price against all the different units of commodity in. such wise that the price exacted for each was equal to the demand price for it and no consumer’s surplus was left to the buyers.”

Joan Robinson calls it perfect discrimination when the monopolist sells each unit of the product at a separate price. Such discrimination is possible only when consumers are sold the units for which they are prepared to pay the highest price and thus they are not left with any consumer’s surplus.

For perfect price discrimination, two conditions are required

(1) To keep the buyers separate from each other, and

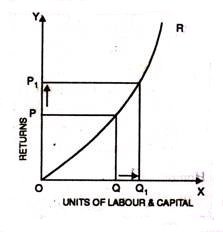

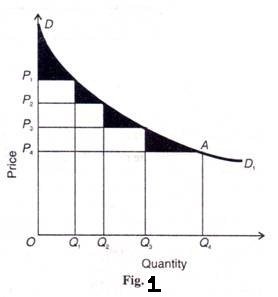

(2) To deal with each buyer on a take-it-or-leave-it basis. When the discriminator of first degree is able to deal with his customers on the above basis, he can transfer the whole of consumers’ surplus to himself. Consider Figure 1. Where DD1 is the demand curve faced by the monopolist. Each buyer is assumed as a price-taker. Suppose the discriminating monopolist sells four units of his product at four different prices:

OQ1 unit at OP1price, Q1Q2 unit at OP2 price, Q2Q3 unit at OP3 price and Q3Q4 unit at OP4 price. The total revenue (or price) obtained by him would be OQ4 AD. This area is the maximum expenditure that the consumers are willing to incur to buy all four units of the product under the first-degree discriminator’s all-or-nothing offer. But with no price discrimination under simple monopoly, the monopolist would sell all four units at the uniform price OP4 and thus obtain the total revenue of OQ4AP4.

This area represents the total expenditure that consumers would actually pay for the four units. Thus the difference between what Quantity the consumers were willing to pay (OQ4 AD) under Fig. 1 the take-it-or-leave-it offer of the first degree discriminator and what they actually pay (OQ4AP4) to the simple monopolist, is consumers’ surplus. This is equal to the area of the triangle DAP4.

Thus under the first-degree price discrimination, the entire consumers’ surplus is pocketed by the monopolist when he charges a separate price for each unit of the product. Price discrimination of the first degree is rare and is to be found in such rare products as diamonds, jewels, precious stones, etc. But a monopolist must have full knowledge of the demand curve faced by him and he should know the maximum price that the consumers are willing to pay for each unit of the product he wants to sell.

Discrimination of the Second Degree (2nd) or Multi-part Pricing

In discrimination of the second degree, the monopolist divides the consumers in different slabs or groups or blocks and charges different prices for different slabs of the same product. Since the earlier units of the product have more utility for the consumers than the later ones, the monopolist charges a higher price for the former units and reduces the price for the later units in the respective slabs.

Such discrimination is only possible if the demand of each consumer below a certain maximum price is perfectly inelastic. Electric supply companies in developed countries practice discrimination of the second degree when they charge a high rate for the first slab of kilowatts of electricity consumed. As more electricity is used, the rate falls with subsequent slabs.

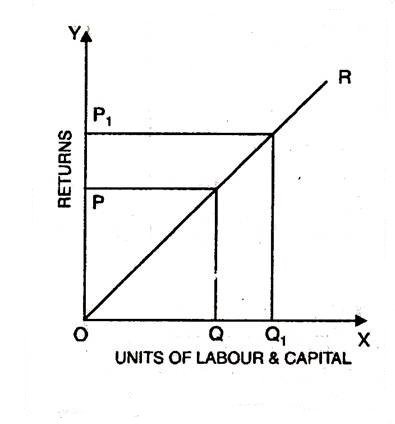

Figure 2 illustrates the second degree discrimination, where DD1is the demand curve for electricity on the part of domestic consumers in a town. CP3 represents the cost of generating electricity, so that the electricity company charges M1P1 rate per kw. up to OM1 units. For consuming the next M1 to М2 units, the rate is lowered to M2P2. The lowest rate charged is M3P3 for M2 to M3 units. M3P3 is, however, the lowest rate which will be charged even if a consumer consumes more than M3 units of electricity.

If the electricity company were to charge only one rate throughout, say M3P3the total revenue would not be maximized. It would be OCP3 M3But by charging different rates for different unit slabs, it gets the total revenue equal to OM3 x P1M1 + OM2 x P2M2 + OM3x P3M3 Thus the second degree discriminator would take away a part of consumers’ surplus covered by the rectangles ABEP1and BCFP2 .The shaded area in three triangles DAP1 Р1ЕР2, and P2FP3 still remains with consumers as their surplus.

The second degree price discrimination is practised by telephone companies, railways, companies supplying water, electricity and gas in developed countries where these services are available in plenty. But it is not found in developing countries like India where such services are scarce.

The differences between the first and second degree price discrimination may be noted. In the first degree discrimination, the monopolist charges a different price for each different unit of the product. But in second degree discrimination, a number of units in one slab (or group or block) are sold at the lowest price and as the slabs increase, the prices charged by the monopolist are lowered. In the case of the former the monopolist takes away the whole of consumers’ surplus. But in the latter case, the monopolist takes away only a portion of the consumers’ surplus and the other portion is left with the buyer.

Conditions under which Price Discrimination is Possible

Price discrimination is possible under following conditions:

- Nature of Commodity

In the first place it is said that price discrimination is possible when the nature of the commodity or service is such that there is no possibility of transference from one market to the other.

That is, the goods sold in the cheaper market cannot be resold in the dearer market; otherwise the monopolist’s purpose will be defeated.

- Distance of Two Markets

Price discrimination is possible when the two markets or markets are separated by large distance or tariff barriers, so that it is not possible to transfer goods from a cheaper market to dearer markets. For instance, a monopolist may sell the same product at a higher price in Bombay and lower price in Meerut.

- Ignorance of the Consumers

Price discrimination is possible when the consumers are ignorant about price discrimination, they are not aware that in one part of the market prices are lower than in the other part. Thus, he purchases in dearer market, than in cheaper market since he is ignorant of the prices that are prevailing in different markets.

- Government Regulation

Price discrimination occurs when the government rules and regulations permit. For instance, according to rules, electricity rates are fixed at higher level for industrial purposes and lower for domestic uses. Similarly, railways charge by law higher fares from first class passengers than from the second class passengers. Hence, price discrimination is possible because of legal sanction.

- Geographical Discrimination

Price discrimination may be possible on account of geographical situations. The monopolist may discriminate between home and foreign buyers by selling at lower price in the foreign market than in the domestic market. Geographical discrimination is possible because no unit of the commodity sold in one market can be transferred to another.

- Difference in Elasticity of Demand

A commodity may have different elasticity of demand in different markets. Thus, the market of a commodity can be separated on the basis of its elasticity of demand.

Hence, a monopolist can charge different prices in different markets classified on the basis of elasticity of demand, low price is charged where demand is more elastic and high price in the market with the less elastic demand or inelastic demand.

- Artificial Difference between Goods

A monopolist may create artificial differences by presenting the same commodity under different names and labels, one for the rich and snobbish buyers and the other for the ordinary customers. For instance, a biscuit manufacturer may wrap small quantity of the biscuits, give it separate name and charge a higher price. Thus, he may charge different price for substantially the same product. He may charge Rs. 2/- for 100 gram wrapped biscuits and Rs. 1.50 for unwrapped biscuits.