Recent World Trade Scenario of Trading

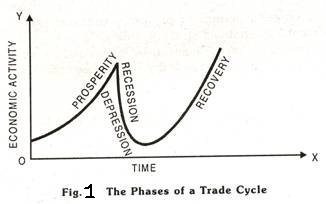

The global economy has been on a subdued growth path since the advent of ‘Financial Crisis’ of 2008, and has now started to show signs of global recovery. In October 2017, the IMF projected world GDP growth to pick up from 3.2% in 2016 to 3.6% in 2017, and further to 3.7% in 2018. Economic activity has also picked up in developed market economies such as the US, UK, and Europe. There is a rise in global demand, which is expected to remain buoyant. The developing and emerging market economies have seen mixed economic performance. The pickup in momentum of global demand has been led by investment demand. More specifically, production of both consumer durables and capital goods have rebounded since the second half of 2016. Some factors that have contributed to these developments include global recovery in investments, led by infrastructure and real estate investment in China; firming global commodity prices; and end of an inventory cycle in US.

On the back of this global recovery, the world is witnessing a pickup in global trade. The Asian Development Bank, in its recent update1, noted that most of the emerging economies (excluding China) are witnessing a rebound in manufacturing exports, “particularly in electronics, where foreign direct investment has been strengthening”. The economies of south-east Asia are also gaining from increased activity along cross-border manufacturing supply chains. The World Trade Organization (WTO), has recently in its September 2017 press release upgraded the growth forecast for global trade in the year 2017, from 2.4% to 3.6%. Particularly, in the first half of 2017, world trade rose by a robust 4.2% (year on year), driven by exports of developing economies which grew by 5.9 percent as compared to a growth of 3.1 percent witnessed in exports of developed economies. Imports by developed and developing economies also increased by 2.1% and 6.9%, respectively. Moreover, the ratio of trade growth to world GDP growth is also set to recover and reach around 1.3, which will be at a highest level in last 5 years.

This pickup in global growth which has boosted demand for imports, spurred intra-Asia-trade as demand was transmitted through global value chains. In this current scenario, even though India is witnessing a mild rebound in its exports, there are concerns that merchandise exports in Asia’s second largest economy are lagging behind other major Asian economies. Today global attention is riveted on emerging and developing economies and especially Asia, driven by the continent’s growing appetite for industrial investment, burgeoning infrastructural requirements and its quest for expanding trade.

Indian economy and its trade scenario

India’s growth story, especially since the start of the 21st century has been remarkable. The Indian economy has come a long way since its economic liberalisation, and is amongst the fastest growing major economies of the world today. While India witnessed a relatively moderate growth during the period 2011-12 to 2013-14, on account of the global economic slowdown, the economy recorded a robust growth averaging 7.5 percent during the period 2014-15 to 2016-17, much above the growth rate of other emerging and developing economies. In the last one year, it has seen major economic policy developments with the introduction of Goods and Services Tax (GST) and demonetization of higher currency notes.

Even though the GDP growth in the first quarter of current fiscal has fallen down to a low of 5.7%, its lowest since March 2014, it is widely believed that the economy has bottomed out and it can only rise from here. According to the IMF, India is expected to grow at 7.2% in this fiscal year, aided by higher government spending and a pickup in the service sector performance.

Fueling India’s growth through international trade

In recent years, India’s robust growth has been driven by the dynamic private sector. An encouraging phenomenon that has been witnessed has been the emergence of a large number of investment driven small and medium enterprises with immense potential for growth. A large number of such enterprises have also endeavoured to expand their business operations overseas. The Indian economy is more globalized than we could imagine. As a result, India’s foreign trade has seen a multi-fold increase, since liberalization of the economy.

Accordingly, there have been significant structural shifts not only in the product basket, but also in the geographical composition of India’s foreign trade. The opening up of Indian economy led to a massive increase in the foreign trade, which aided in sustained GDP growth over last two decades. During the last 25 years Indian exports have increased by 17 times and imports by 19 times. India’s share in global merchandise exports has risen from 0.6 percent in early 1990s to 1.7 percent in 2016, and similarly the share of imports has risen from 0.6 percent to 2.4 percent during the same period. India’s trade to GDP ratio, a measure of an economy’s openness and integration into the global economy, has witnessed a phenomenal increase over the last few decades. Foreign trade which constituted around 13-15 percent of India’s GDP in the early nineties, peaked at 55 percent in 2012- 13 and today accounts for around 40 percent in 2016-17. India also, ranked as the 20th largest exporter and 14th largest importer in the world in 2016.

Concomitantly, India’s engagement with Global Value Chains (GVCs), which have become dominant feature of world trade, has increased significantly since 1990s. In manufacturing sector, especially for electrical and optical equipment, India is more integrated with the south east Asian region, while for services the integration in GVCs is with western countries like the US and UK. According to an OECD estimate, developing economies with fastest growing GVC participation have experienced a GDP per capita growth rate percent above average.

India has set an ambitious target of achieving exports worth US $ 900 billion by 2020, while accounting for a share of 3.5 percent of global exports4. In the current global macroeconomic scenario, while it seems like a challenging task, concerted efforts would need to be made for India to be able to achieve its trade target and realign its foreign trade policy with the new global trading system.

While the global economic scenario is crucial, the domestic factors are no less important, when it comes to trade. India’s overall trade policy faces certain challenges viz. inadequate export diversification in terms of products and geographical distribution; insignificant involvement of a majority of states in exports; rationalisation of the tariff regime and export promotion schemes; and factor market reforms which are critically linked with export performance. These challenges not only affect the productivity and competitiveness of domestic firms but also restrict them from participating in global production networks.

(i) Integrating into and moving up the value chain

Most manufactured products, often high technology manufactured products, that are part of GVCs are infrastructure critical products whose parts are manufactured in several countries. A robust transport and connectivity network supported by fast entry/exit through port/customs is a precondition to making such products as delay may disrupt the entire value chain. There is a need for India to focus on expanding production capacity along with value addition, and moving up the value chain,while creating an enabling environment to account for a sizeable share in major leading global exports. This gain seven more significance given that India’s labour force is projected to swell by about 110 mn by 2020. The biggest challenge is to employ the surplus labour coming out of agriculture into industry and services.

(ii) Upscaling Manufacturing

The Make in India initiative is an important initiative of the Government of India, which envisages to promote India as a manufacturing hub and investment destination. There is need for highlighting the potential and stimulating the manufacturing sector through supporting mechanisms and conducive policy measures, including support for R&D, technology orientation and investment incentives. A Higher expenditure on R&D generally correlates with increase in high-technology exports, and increased local value addition. R&D expenditure as a percentage share of GDP in India has remained extremely low at less than1 percent, much lower even in comparison to other developing economies. Also, while we lay emphasis on the manufacturing sector and thereby on manufactured exports, it is also important to ensure an enabling environment and improving our competitiveness by investing in infrastructure such as better connectivity through roads and ports, coal availability, labour reforms and flexibility in factor markets.

(iii) Aligning India’s Export Capability in-Line with Global Import Demand

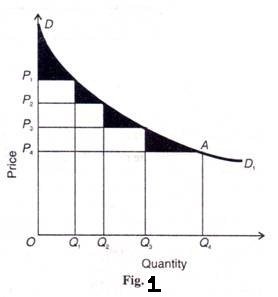

With regard to India’s exports, while merchandise exports have more than doubled over the period 2006-07 to 2016-17 from US$ 126 billion to more than US$276 billion, there remains huge potential for exports of select products to select countries in line with India’s export capability and import demand. There is need for identifying and aligning India’s export capability vis-à-vis global import demand. Such in-depth analysis has been the focus of research studies in Exim Bank. Comparative analyses of global trends in trade, undertaken in such studies have yielded interesting results.

To Conclude

All in all, a pick-up in global growth is expected to contribute to the revival of international trade, but the downside risks such as the possible adoption of protectionist trade policies by especially developed market economies, around the world weigh on the recovery of trade. As a result, there is an increasing need for India and other emerging market economies, relying on export led economic growth, to take a proactive stand for globalization and international trade.

There is a need to shift our focus from exporting what we can (or supply based), to items that are globally demanded. A demand-based export basket diversification approach could give a big push to exports. While India has made remarkable progress in the recent past, it facesan even more challenging global environment today. Itis certainly a daunting, yet possible, task to ensure that India repositions itself as an important driver of global economic growth.