Changes in Income and Balance of Payments Adjustment:

Just as the exchange rate and price changes can influence the balance of payments situation of a country, the variations in income too can affect balance of payments disequilibrium in a very significant way.

Given the domestic price level and exchange rate, higher incomes at home tend to raise the imports, while the higher incomes abroad result in an increase in the volume of exports of the country. Thus, an improvement in the balance of payments deficit can be affected either through a contraction in domestic income or an expansion in incomes in foreign countries.

In an open economic system, the income- expenditure identity can be stated as:

Y ≡ Cd + Id + Xd ….(i)

The subscript d in the equation denotes production out of domestic resources. The income in an open economy can also be visualised as the sum of consumption of domestic goods (Cd), the amount spent on imports (M) and the saving (S).

Y ≡ Cd + M + S ….(ii)

From (i) and (ii) we get-

Cd + Id + Xd ≡ Cd + M + S

Or Id + Xd ≡ M + S

Or Xd – M ≡ S – Id

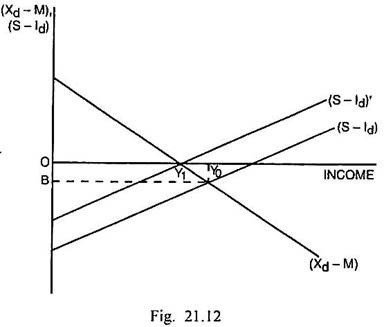

Assuming that exports and investment are autonomous and imports and saving are the direct functions of income, the impact of income changes upon the balance of payments can be shown through Fig. 21.12.

Initially, the equilibrium determined by the intersection between (Xd – M) and (S – Id) function is at Y0 level of income with the balance of payments deficit equal to OB. A fall in the level of income from Y0 to Y1 will bring about a decline in the amount of saving.

Consequently, (S – Id) function will shift to the left and the equilibrium between (Xd – M) and (S – Id)’ takes place at Y1 lower level of income where the payments deficit has completely disappeared. Thus the appropriate changes in income can ensure an improvement in the balance of payments situation of a country.

Balance of Payments Adjustment through Capital Movements:

The international capital movements can significantly influence the balance of payments situation of a country. Kindelberger has made a distinction between the short-term and long-term capital movements.

According to him, “A capital movement is short term, if it is embodied in a credit instrument of less than a year’s maturity. If the instrument has a duration of more than a year or consists of a title to ownership, such as a share or stock or a deed to property, the capital movement is long term.” But the distinction, according to instrument, does not really indicate whether a capital movement is temporary or quasi- permanent.

The European speculators in the New York Stock Market in the 1920’s used the instruments of long-term investment equity shares in companies but these demonstrated a high rate of turnover and only a brief loss of liquidity.

Similarly, a European central bank that buys United States government bonds rather than short term bills is still holding monetary reserves and not making a real long-term investment. The short- term instruments are typically the Central Bank deposits, commercial bank deposits, bills, acceptances, overdrafts, open book credit, and even bank notes.

Under the nineteenth century gold standard, the rate of interest caused the movement of short- term capital and played a considerable part in bringing about adjustment in the balance of payments. During the inter-war period, however, the short term capital movements came to be regarded as a menace to the international stability rather than as an instrument of adjustment.

Under the conditions similar to those which prevailed during that period, the import surplus leads to capital outflow and increased loss of reserves rather than to the inflow which can finance the balance of payments on current account. Conversely, an export surplus, through a rising exchange rate and reduced rate of interest, leads not to the off-setting capital outflow, but to a capital inflow that brings about an embarrassing addition to gold and exchange reserves, excess banking reserves and monetary super-abundance.

The short-term capital movements cannot resolve the balance of payments difficulties. They can only provide a temporary relief. But even such relief is extremely useful since it provides a cushion; while the changes that can provide a permanent remedy are brought about. The long term capital includes bonds, bank loans and direct investments. The movements of long term capital of a normal character are required to achieve the long term balance of payments equilibrium.

A young debtor country borrows; imports more than it exports ; maintains a foreign exchange rate over-valued in terms of static equilibrium and has too high a level of national money income ; too large a money supply, too much investment in relation to domestic saving, too high prices, too low a rate of interest.

The equilibrium in respect of international payments requires that the capital movements take the form and direction which are appropriate to time period. If a young borrowing country borrows short-term capital and adjusts to the flow as if it were a long-term capital movement, the national income, foreign exchange rate and other variables may be in equilibrium except the balance of payments.

In this situation, imports exceed exports and domestic investment is larger than savings by this amount. If long-term capital movements are called for but only short-term capital is available, the dynamic balance of payments equilibrium cannot be achieved. Such an equilibrium is possible, if the balance of trade deficit is bridged up by an appropriate inflow of autonomous long-term capital.

Domestic Price Changes and Balance of Payments Adjustment:

In the analysis concerning the changes in exchange rates, we took an over-simplified assumption that the home prices of depreciating country’s exports and foreign prices of her imports do not undergo changes as a result of depreciation.

In fact depreciation or devaluation amounts to the lowering of the domestic price level relative to the foreign level. It is actually such changes in the relative price level at home and abroad that cause, in a large or small measure, an increase in exports and a contraction in imports.

Similar changes can definitely be effected through the differential rates of absolute price changes at home and abroad, while maintaining the foreign exchange rate stable. A decline in the domestic price level to the extent of, say 10 percent, the exchange rate remaining unchanged, has the same effect as the devaluation of the home currency vis-a-vis foreign currencies by 10 percent.

It, however, does not mean that devaluation and internal deflation have exactly similar effects in other respects too. The two are certainly different in their effects upon the economic system in the short and long periods. The intensity of their impact upon the general economic activity within the economy is likely to be vastly different.

The degree by which changes in absolute domestic price level can be successful in reducing the balance of payments deficit is contingent upon the elasticities of demand for imports at home and abroad. With the fall in the prices of export goods, given an elastic demand for imports of these products in foreign countries, the increase in exports will be relatively large. The increased receipts now available from exports will tend to improve the payments deficit.

A fall in the internal price level vis-a-vis price level abroad leads invariably to some decline in imports which by reducing the demand for foreign exchange also contributes in the reduction of payments deficit. But the extent to which internal deflation lowers the demand for foreign products depends upon the cross elasticity of demand between the foreign and the domestic products. Greater this elasticity coefficient, more sizeable will be the contraction in imports and vice-versa.

Balance of Payments Adjustment through Expenditure Policies:

A deficit in the balance of payments entails an excess of expenditure over income. In order to correct it, there is a need to equalise the two.

Two types of policies concerning expenditure can be adopted to this end:

(a) Expenditure-reduction policies; and

(b) Expenditure-switching policies.

(a) Expenditure-Reduction Policies:

A policy of expenditure-reduction or a reduction in aggregate demand can be implemented through taxes or higher interest rates. As the expenditure is lowered, a part of reduction in expenditure affects the domestic production. This brings multiplier in operation, through which the expenditure and output get further reduced.

A policy of expenditure-reduction can have both direct and induced effects. The direct effect of such policies is favourable. The induced effect through lower output and consequently lower expenditure, however, will be unfavourable so long as a reduction in income reduces expenditure by a smaller amount, that is, if the marginal propensity to spend is less than one. Greater the initial reduction in expenditure falls on imports, smaller will be adverse effect of such policies.

Thus, so long as the marginal propensity to spend is less than unity, the net effect of an expenditure-reduction policy will be an improvement in the balance of payments deficit.

The expenditure reduction policies may include:

(i) Expenditure reducing monetary policy which is comprised of reduction in the supply of money and credit and increase in interest rates.

(ii) Expenditure reducing fiscal policy which is comprised of reduced government spending and increase in taxes.

As the central bank restricts money supply and raises interest rates, there is reduction in investment and income. It leads to a fall in aggregate demand for imported goods. A higher structure of interest rates also induces inflow of capital from abroad and restricts outflow of capital from the home country. Thus the expenditure-reduction monetary policy can result in the off-setting of BOP deficit.

The elimination of BOP deficit may also be brought through reduced government expenditure on imports and increase in import duties and other taxes lowering the aggregate demand. The restrictive fiscal policy will cause a decline in investment and consequent decline also in income and aggregate demand. Thus expenditure reducing fiscal policies will remove the deficit in the international payments.

The effect of expenditure reducing monetary and fiscal policy on BOP deficit is explained through Figs. 21.13 and 21.14.

In Fig. 21.13, given originally IS0 and LM0 functions, the equilibrium income is Y0 and rate of interest is r0. B = 0 is the balance of payments line. The equilibrium takes place below the BOP line signifying the BOP deficit.

The adoption of expenditure reducing monetary policy including reduction in the supply of money and increase in interest rates causes the shift in LM function to LM1. The equilibrium between IS0 and LM1 takes place exactly at the balance of payments line with lower income Y0 and higher rule of interest r0.

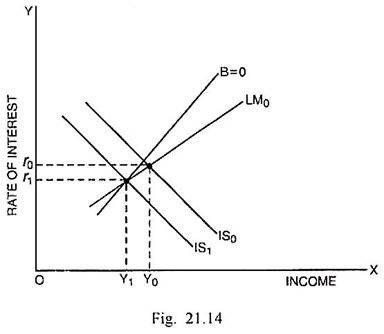

In Fig. 21.14, IS0 and LM0 determine originally the equilibrium income Y0 and rate of interest r0. The equilibrium takes place below the BOP line (B = 0) indicating deficit in the BOP. The government follows the policies of expenditure reduction and higher taxes.

Consequently, the IS function shifts to the left to IS1. The intersection of IS1 and LM0 takes place exactly at the balance of payments line (B = 0). Thus the BOP deficit gets removed and the new equilibrium takes place at the lower level of income Y1.

In this connection, two further points should also be made. Firstly, an expenditure reduction, by reducing the country’s imports, will bring about multiple reduction in incomes abroad which in turn will reduce the foreign spending on the country’s exports.

As a result, the domestic output will decline. This is generally known as repercussion effect. It was analysed by F. Machlup in his work, International Trade and the National Income Multiplier. Secondly, the reduction in expenditure and output may bring down the domestic price level. It may cause a switch of spending between the foreign and domestic goods.

(b) Expenditure-Switching Policies:

The policy of switching expenditure away from the foreign produced goods towards the home produced goods will have the effect of raising the level of domestic production. So long as the marginal propensity to spend is less than unity, it will bring about an improvement in the payments deficit.

We can make a distinction between two types of expenditure-switching policies. One is devaluation, which by making the country’s goods relatively cheaper compared with foreign goods, will tend to switch both domestic and foreign expenditures towards the home-produced goods.

The other is the use of import restrictions, which tends to divert the spending of domestic consumers, now unable to buy foreign-produced goods, towards the home-produced substitutes of foreign products. The controls may also be imposed sometimes to stimulate exports or, in other words, to induce the foreigners to switch their spending towards domestic output.

Whatever is the expenditure-switching policy, the aim always is to raise the demand for domestic output. This poses the questions- wherefrom will come the additional output to meet the requirements of additional demand? This problem can be investigated in relation to three possible cases.

The first is the case in which domestic economy is afflicted by wide-spread unemployment. In such a case, a switch of demand towards home-produced goods will ensure an increase in domestic output and income through the increased utilization of unemployed resources.

The second case is one in which, there is a state of full employment in the economy and the policy of expenditure-switching is backed by a policy of reducing the aggregate demand. This combination of policies can ensure the balance of payments equilibrium without sacrificing full employment.

However, a policy of reduction in aggregate demand can result in unemployment at home. In that case, the accompanying policy of switch of expenditure from foreign-produced goods to home-produced goods is employed to remove any such possibility of unemployment.

The third case is one in which the expenditure- switching policy is adopted in a state of full employment. In this case, the switch policy is not supplemented by the expenditure-reducing policy and, therefore, the inflationary consequences will follow.

Balance of Payments Adjustment through Capital Movements:

The international capital movements can significantly influence the balance of payments situation of a country. Kindelberger has made a distinction between the short-term and long-term capital movements.

According to him, “A capital movement is short term, if it is embodied in a credit instrument of less than a year’s maturity. If the instrument has a duration of more than a year or consists of a title to ownership, such as a share or stock or a deed to property, the capital movement is long term.” But the distinction, according to instrument, does not really indicate whether a capital movement is temporary or quasi- permanent.

The European speculators in the New York Stock Market in the 1920’s used the instruments of long term investment equity shares in companies but these demonstrated a high rate of turnover and only a brief loss of liquidity.

Similarly a European central bank that buys United States government bonds rather than short term bills is still holding monetary reserves and not making a real long-term investment. The short- term instruments are typically the Central Bank deposits, commercial bank deposits, bills, acceptances, overdrafts, open book credit, and even bank notes.

Under the nineteenth century gold standard, the rate of interest caused the movement of short- term capital and played a considerable part in bringing about adjustment in the balance of payments. During the inter-war period, however, the short term capital movements came to be regarded as a menace to the international stability rather than as an instrument of adjustment.

Under the conditions similar to those which prevailed during that period, the import surplus leads to capital outflow and increased loss of reserves rather than to the inflow which can finance the balance of payments on current account. Conversely, an export surplus, through a rising exchange rate and reduced rate of interest, leads not to the off-setting capital outflow, but to a capital inflow that brings about an embarrassing addition to gold and exchange reserves, excess banking reserves and monetary super-abundance.

The short-term capital movements cannot resolve the balance of payments difficulties. They can only provide a temporary relief. But even such relief is extremely useful since it provides a cushion; while the changes that can provide a permanent remedy are brought about. The long term capital includes bonds, bank loans and direct investments. The movements of long term capital of a normal character are required to achieve the long term balance of payments equilibrium.

A young debtor country borrows; imports more than it exports ; maintains a foreign exchange rate over-valued in terms of static equilibrium and has too high a level of national money income ; too large a money supply, too much investment in relation to domestic saving, too high prices, too low a rate of interest.

The equilibrium in respect of international payments requires that the capital movements take the form and direction which are appropriate to time period. If a young borrowing country borrows short-term capital and adjusts to the flow as if it were a long-term capital movement, the national income, foreign exchange rate and other variables may be in equilibrium except the balance of payments.

In this situation, imports exceed exports and domestic investment is larger than savings by this amount. If long-term capital movements are called for but only short-term capital is available, the dynamic balance of payments equilibrium cannot be achieved. Such an equilibrium is possible, if the balance of trade deficit is bridged up by an appropriate inflow of autonomous long-term capital.

Balance of Payments Adjustment through Controls:

The improvement in the balance of payments deficit may be effected through controls which can be classified under two heads financial controls and commercial controls. According to H.G. Johnson, “Financial controls operate through control over the use of money, by restricting the freedom of use of domestic money either through regulation of certain uses (as in the case of multiple exchange rates) or by making some uses of money more expensive than others. Commercial controls, on the other hand, operate on the goods side of transactions by preventing people from buying certain goods or forcing them to buy others, or providing financial incentives (tariffs, subsidies) for certain kinds of sales or purchases.”

Whatever the character of controls and whether these are applied to exports or imports, their major effect is to create a divergence between the internal and external values of commodities. While export restrictions reduce the internal values of goods relatively to the external values, import restraints act in the opposite manner.As compared with devaluation, controls raise two important questions. The first is concerned with the effectiveness of controls in increasing net foreign exchange earnings.

H.G. Johnson evaluates the relative effectiveness of the two in the following words, “Roughly we can think of devaluation as being the equivalent of an import duty and an export subsidy and an import duty is bound to save foreign exchange, whereas an export subsidy will save foreign exchange or not according to whether the elasticity of demand for the country’s exports is greater or less than one. Thus an import duty by itself will only save foreign exchange to a lesser extent than devaluation, if an export subsidy would actually reduce the country’s earnings from exports that is, if the foreign elasticity of demand for exports were less than unity, the country should of course restrict rather than encourage exports. An export subsidy by itself would always be worse than a devaluation, since it would fail to obtain the necessarily favourable effect of devaluation in reducing the amount spent on imports.”

The second question is concerned with the welfare implication of controls versus devaluation. The choice between the two, H.G. Johnson holds, depends on the relation between the existing degree of controls and the optimum degree of trade restraints. In a situation when a country has unexploited monopoly or monopsony power, it stands to be benefitted through the exploitation of this power and through further trade restrictions.

If the restrictions have already been carried beyond the optimum level, the benefit will accrue through the liberalisation of trade restrictions. The controls can also provoke the retaliation from other countries which may nullify any beneficial effect of such controls either upon the balance of payments or upon the welfare of the community.

Considering retaliatory trade restrictions completely futile, H.G. Johnson records “….it is obvious that it will never pay two countries to have trade barriers against each other. Such barriers could always be cleared down to a barrier on the part of one country only, to the benefit of both, and possibly they could be completely eliminated. If international income transfers were possible, freedom of trade could always be more beneficial than the preservation of barriers.”

To sum up, an appropriate blend of all the measures can ensure improvement in the balance of payments situation of a country.