Investment Strategies

An investment strategy is what guides an investor’s decisions based on goals, risk tolerance, and future needs for capital. Some investment strategies seek rapid growth where an investor focuses on capital appreciation, or they can follow a low-risk strategy where the focus is on wealth protection.

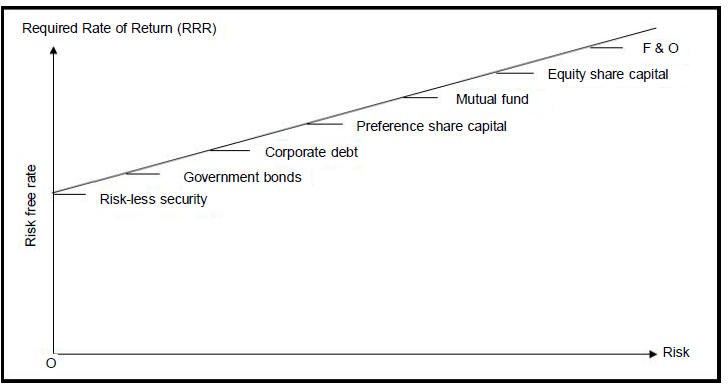

In finance, an investment strategy is a set of rules, behaviors or procedures, designed to guide an investor’s selection of an investment portfolio. Individuals have different profit objectives, and their individual skills make different tactics and strategies appropriate. Some choices involve a tradeoff between risk and return. Most investors fall somewhere in between, accepting some risk for the expectation of higher returns.

Many investors buy low-cost, diversified index funds, use dollar-cost averaging, and reinvest dividends. Dollar-cost averaging is an investment strategy where a fixed dollar amount of stocks or a particular investment are acquired on a regular schedule regardless of the cost or share price. The investor purchases more shares when prices are low and fewer shares when prices are high. Over time, some investments will do better than others, and the return averages out over time.

Some experienced investors select individual stocks and build a portfolio based on individual firm analysis with predictions on share price movements.

Strategies

- No strategy: Investors who don’t have a strategy have been called Sheep. Arbitrary choices modeled on throwing darts at a page (referencing earlier decades when stock prices were listed daily in the newspapers) have been called Blind Folded Monkeys Throwing Darts [no source]. This famous test had debatable outcomes.

- Active vs Passive: Passive strategies like buy and hold and passive indexing are often used to minimize transaction costs. Passive investors don’t believe it is possible to time the market. Active strategies such as momentum trading are an attempt to outperform benchmark indexes. Active investors believe they have the better than average skills.

- Momentum Trading: One strategy is to select investments based on their recent past performance. Stocks that had higher returns for the recent 3 to 12 months tend to continue to perform better for the next few months compared to the stocks that had lower returns for the recent 3 to 12 months. There is evidence both for and against this strategy.

- Buy and Hold: This strategy involves buying company shares or funds and holding them for a long period. It is a long term investment strategy, based on the concept that in the long run equity markets give a good rate of return despite periods of volatility or decline. This viewpoint also holds that market timing, that one can enter the market on the lows and sell on the highs, does not work for small investors, so it is better to simply buy and hold.

- Long Short Strategy: A long short strategy consists of selecting a universe of equities and ranking them according to a combined alpha factor. Given the rankings we long the top percentile and short the bottom percentile of securities once every re-balancing period.

- Indexing: Indexing is where an investor buys a small proportion of all the shares in a market index such as the S&P 500, or more likely, an index mutual fund or an exchange-traded fund (ETF). This can be either a passive strategy if held for long periods, or an active strategy if the index is used to enter and exit the market quickly.

- Pairs Trading: Pairs trade is a trading strategy that consists of identifying similar pairs of stocks and taking a linear combination of their price so that the result is a stationary time-series. We can then compute Altman_Z-score for the stationary signal and trade on the spread assuming mean reversion: short the top asset and long the bottom asset.

- Value vs Growth: Value investing strategy looks at the intrinsic value of a company and value investors seek stocks of companies that they believed are undervalued. Growth investment strategy looks at the growth potential of a company and when a company that has expected earnings growth that is higher than companies in the same industry or the market as a whole, it will attract the growth investors who are seeking to maximize their capital gain.

- Dividend growth investing: This strategy involves investing in company shares according to the future dividends forecast to be paid. Companies that pay consistent and predictable dividends tend to have less volatile share prices. Well-established dividend-paying companies will aim to increase their dividend payment each year, and those who make an increase for 25 consecutive years are referred to as a dividend aristocrat. Investors who reinvest the dividends are able to benefit from compounding of their investment over the longer term, whether directly invested or through a Dividend Reinvestment Plan (DRIP).

- Dollar cost averaging: The dollar cost averaging strategy is aimed at reducing the risk of incurring substantial losses resulted when the entire principal sum is invested just before the market falls.

- Contrarian investment: A contrarian investment strategy consists of selecting good companies in time of down market and buying a lot of shares of that company in order to make a long-term profit. In time of economic decline, there are many opportunities to buy good shares at reasonable prices. But what makes a company good for shareholders? A good company is one that focuses on the long-term value, the quality of what it offers or the share price. This company must have a durable competitive advantage, which means that it has a market position or branding which either prevents easy access by competitors or controls a scarce raw material source. Some examples of companies that response to these criteria are in the field of insurance, soft drinks, shoes, chocolates, home building, furniture and many more. We can see that there is nothing “fancy” or special about these fields of investment: they are commonly used by each and every one of us. Many variables must be taken into consideration when making the final decision for the choice of the company. Some of them are:

- The company must be in a growing industry.

- The company cannot be vulnerable to competition.

- The company must have its earnings on an upward trend.

- The company must have a consistent return on invested capital.

- The company must be flexible to adjust prices for inflation.

- Smaller companies: Historically medium-sized companies have outperformed large cap companies on the Stock market. Smaller companies again have had even higher returns. The very best returns by market cap size historically are from micro-cap companies. Investors using this strategy buy companies based on their small market cap size on the stock exchange. One of the greatest investors, Warren Buffett, made money in small companies early in his career combining it with value investing. He bought small companies with low P/E ratios and high assets to market cap.