Supply refers to the quantity of a good or service that producers are willing and able to offer for sale in the market at various prices over a specific period of time. It is a fundamental concept in economics that reflects the relationship between price and the quantity supplied. Generally, supply increases with rising prices because higher prices provide greater incentives for producers to produce more, while supply decreases when prices fall. Factors affecting supply include production costs, technology, government policies, and market conditions. The law of supply states that, ceteris paribus, the quantity supplied of a good rises as its price increases.

Suppliers must anticipate price changes and quickly react to changes in demand or price. However, some market factors are hard to predict. For instance, the yield of commodities cannot be accurately estimated, yet their yields strongly affect prices.

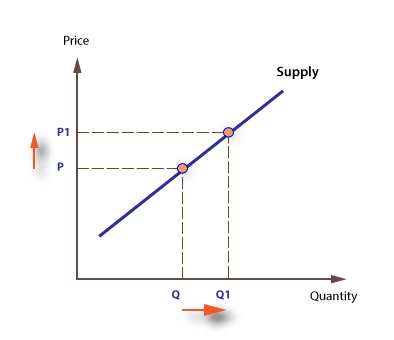

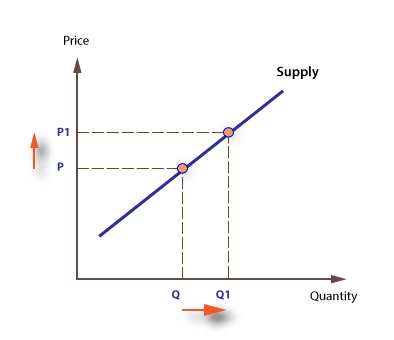

When the price of a product is low, the supply is low. When the price of a product is high, the supply is high. This makes sense because companies are seeking profits in the market place. They are more likely to produce products with a higher price and likelihood of producing profits than not.

Determinants of Supply:

Supply refers to the quantity of a good or service that producers are willing to sell at different prices during a given period. The supply of a product is not determined by price alone—it is influenced by a wide range of factors. These are called the determinants of supply.

The price of a product is a fundamental determinant of supply. Higher prices increase the incentive for producers to supply more to earn greater profits. Conversely, lower prices reduce profitability, leading to a reduction in the quantity supplied. This forms the basis of the Law of Supply, which states that supply increases with price and decreases when price falls, all else being equal.

The cost of inputs—such as raw materials, labor, fuel, and machinery—directly impacts supply. If the cost of production rises, the profit margin decreases, and producers may reduce the quantity supplied. On the other hand, a fall in production costs makes production more profitable, encouraging firms to increase output and supply more products to the market.

Advancements in technology enable more efficient production processes. Improved machinery and methods increase productivity, reduce waste, and lower costs. This enhances the firm’s ability to produce more with the same or fewer resources, thereby increasing supply. For example, automation in manufacturing can significantly raise output levels and supply in a shorter period.

The supply of a product may be affected by the prices of related goods, especially in case of alternative or jointly produced goods. If a firm can produce multiple products using the same resources, an increase in the price of one product may cause it to switch production, reducing the supply of the other. Similarly, if two goods are jointly produced (like meat and leather), a change in one can affect the supply of both.

- Number of Sellers in the Market

An increase in the number of suppliers generally leads to a higher total market supply, assuming each contributes some quantity. Conversely, if firms exit the industry due to losses or other barriers, the supply in the market falls. Therefore, the structure and competitive intensity of the market play a key role in determining supply levels.

- Government Policies (Taxes and Subsidies)

Government interventions like taxes and subsidies significantly influence supply. A tax raises production costs and may reduce supply. On the other hand, a subsidy reduces the cost of production, encouraging producers to supply more. Regulatory policies, price controls, and business licensing rules also affect the firm’s capacity and willingness to supply goods.

- Expectations of Future Prices

Producers often base their current supply decisions on expectations about future market conditions. If prices are expected to rise in the future, firms may reduce current supply to sell more at higher prices later. If prices are expected to fall, they may increase current supply to avoid future losses. Thus, anticipations regarding market trends influence supply decisions.

- Natural and Climatic Conditions

For industries like agriculture and mining, supply is heavily dependent on environmental factors. Good weather leads to bumper harvests and higher supply, while floods, droughts, or natural disasters can damage production and reduce supply. Climate patterns and long-term environmental changes also influence seasonal and geographical supply capabilities.

- Infrastructure and Logistics

The efficiency of transport, storage, and communication systems influences how much and how quickly goods can be supplied. Good infrastructure reduces delays, lowers costs, and improves access to markets, thereby increasing supply. In contrast, poor infrastructure raises transaction costs and disrupts the flow of goods, limiting supply potential.

- Availability of Production Inputs

The easy and timely availability of key inputs like skilled labor, raw materials, capital, and equipment determines how smoothly a firm can produce. A shortage or difficulty in accessing these inputs can hinder production, reducing the supply of goods. Conversely, an abundance of resources allows for higher production and greater supply.

Factors of Supply:

The factors of supply for a given product or service is related to:

- The price of the product or service

- The price of related goods or services

- The prices of production factors

- The price of inputs

- The number of production units

- Production technology

- Expectations of producers

- Government policies

- Random, natural or other factors

In the goods market, supply is the amount of a product per unit of time that producers are willing to sell at various given prices when all other factors are held constant. In the labor market, the supply of labor is the amount of time per week, month, or year that individuals are willing to spend working, as a function of the wage rate.

In financial markets, the money supply is the amount of highly liquid assets available in the money market, which is either determined or influenced by a country’s monetary authority. This can vary based on which type of money supply one is discussing.

Factors affecting supply:

The price of a product is a primary factor influencing supply. Higher prices motivate producers to supply more, as they can earn greater profits. On the contrary, lower prices may discourage production since the revenue generated might not cover costs. Therefore, there is a direct relationship between price and quantity supplied—this forms the basis of the law of supply in economics.

The cost of production includes expenses on raw materials, labor, machinery, and energy. When these costs rise, profit margins shrink, discouraging production and reducing supply. Conversely, a decrease in production costs enhances profitability, encouraging producers to increase output. As a result, fluctuations in input costs have a significant impact on the supply levels in the market, especially for price-sensitive goods.

Improved technology enhances production efficiency, allowing firms to produce more output with the same or fewer inputs. It reduces wastage, lowers costs, and increases productivity. This leads to an increase in the supply of goods and services. For instance, automation in manufacturing industries or innovations in agriculture can significantly boost supply by reducing time, cost, and effort involved in production processes.

When producers have the option to produce different products using similar resources, the relative prices of these goods influence their decision. If the price of one product increases, producers may shift resources toward that product to maximize profits, reducing the supply of others. For example, a rise in the price of soybeans may lead farmers to cultivate more soybeans instead of wheat, affecting wheat supply.

Government intervention through taxes, subsidies, and regulations can directly influence supply. Subsidies reduce production costs, thereby encouraging producers to increase output. On the other hand, higher taxes or strict compliance regulations increase costs and discourage production. Government-imposed price controls, quotas, and licensing requirements also impact the willingness and ability of firms to supply goods in the market.

Weather and environmental factors play a crucial role, especially in sectors like agriculture and fisheries. Favorable weather conditions can lead to abundant harvests and increased supply. On the contrary, droughts, floods, earthquakes, and other natural calamities disrupt production and logistics, reducing supply. Long-term changes like climate change also influence agricultural and natural resource-based supply chains over time.

The total supply in the market depends on how many producers are actively supplying a product. An increase in the number of sellers usually results in an increased supply, leading to greater market competition. Conversely, if firms exit the market due to poor profitability or barriers to entry, the overall supply decreases. Hence, market structure and the presence of sellers significantly influence supply levels.

Producers’ expectations about future prices, demand, and market conditions influence their current supply decisions. If they expect prices to rise, they may withhold current output to benefit from higher future prices. In contrast, if prices are expected to fall, producers may increase current supply to sell goods before the price drops. Thus, anticipations and market outlook play a crucial role in supply management.

- Availability of Inputs and Raw Materials

The easy availability of inputs like labor, capital, and raw materials facilitates smooth production. If there is a shortage or delay in obtaining inputs, production slows down, reducing supply. Similarly, the cost and accessibility of inputs affect how much a firm can produce. Supply chains that are efficient and reliable ensure continuous input flow and help maintain consistent supply levels in the market.

- Infrastructure and Transportation

Efficient infrastructure like roads, warehouses, and communication systems affects the speed and cost of supplying goods. Better infrastructure reduces transit times and spoilage, especially for perishable goods. Improved transportation networks also expand market reach, allowing firms to supply larger areas effectively. Poor or underdeveloped infrastructure increases costs, delays delivery, and disrupts supply chains, thereby lowering the volume of goods supplied.

Supply function assumptions

- Constant returns to scale could be permitted, in which case, if profit maximization at a nonzero output is possible at all, then it necessarily occurs at all levels of output.

- Shifting from the short-run to the long-run context imposes a second form of assumption modification. This requires the elimination of all fixed inputs so that each b il = 0, and the inclusion of the long-run equilibrium condition π il = 0 for every firm.

- A third possibility for assumption modification is the introduction of imperfectly competitive elements that give firms some influence over the prices they charge for their outputs.

Like this:

Like Loading...