Production, Meaning, Factors of Production, Production Function, Features, Types

Production is a fundamental economic activity that involves transforming inputs into outputs to satisfy human wants and needs. It refers to the creation of utility by converting raw materials, natural resources, and various inputs such as labor and capital into finished goods or services. The term “production” is not confined only to manufacturing physical products but also includes the provision of services like healthcare, education, transportation, and banking.

In economics, production is defined as any activity that results in the generation of value. It adds utility in terms of form (changing the shape or structure of goods), place (making goods available where they are needed), and time (making goods available when they are required). For instance, converting cotton into fabric or providing consultancy services both fall under the scope of production.

Production plays a central role in the functioning of any economy. It is the backbone of economic development, as it creates goods and services, generates income, provides employment, and contributes to the GDP. The process involves the effective combination and utilization of the four factors of production—land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurship.

Efficient production ensures cost-effectiveness, quality output, and customer satisfaction. In a competitive business environment, firms continuously seek to improve their production processes through innovation and technology. Thus, production is not merely a technical activity but also a strategic function that directly influences business performance and market success.

Factors of Production:

-

Land

Land refers to all natural resources used in the creation of goods and services. This includes physical land, forests, minerals, water, and other gifts of nature. It is a passive factor but essential, as it provides the base for agriculture, manufacturing, and infrastructure. The availability and productivity of land influence industrial location and output. It is fixed in supply and subject to diminishing returns if overused without improvement or technological intervention.

-

Labour

Labor represents the human effort—both physical and mental—used in production. It includes the work of employees, professionals, and skilled or unskilled workers. The productivity of labor depends on education, health, skills, motivation, and working conditions. Labor is an active factor that contributes directly to the creation of goods and services. Effective labor management and training programs can enhance output, efficiency, and innovation, making labor a critical resource in competitive business environments.

-

Capital

Capital comprises man-made resources such as tools, machinery, buildings, and technology used to produce other goods and services. It differs from money, as capital refers specifically to physical assets that facilitate production. Capital improves labor productivity and production efficiency. It can be categorized into fixed capital (long-term assets) and working capital (short-term inputs). Businesses must invest in and maintain capital assets to scale operations and stay technologically competitive in dynamic markets.

- Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship is the ability to identify opportunities, organize resources, take risks, and innovate. Entrepreneurs combine land, labor, and capital to initiate and manage production activities. They are the decision-makers who determine what, how, and for whom to produce. Successful entrepreneurs drive innovation, generate employment, and stimulate economic growth. Their risk-taking ability and vision are essential for launching new ventures and sustaining businesses in a changing economic landscape.

- Human Capital

Human capital refers to the knowledge, skills, experience, and competencies possessed by individuals. Unlike labor, which measures effort, human capital emphasizes quality and expertise. Investment in education, training, and healthcare improves human capital, leading to higher productivity and innovation. In knowledge-driven economies, human capital is crucial for sectors like IT, R&D, and services. Businesses that cultivate strong human capital gain a strategic advantage through creativity, efficiency, and decision-making capabilities.

- Information and Knowledge

Information and knowledge have become key production factors in the digital era. Access to market data, consumer insights, and industry trends enables firms to make informed decisions and respond to changes swiftly. Knowledge fuels innovation, strategy, and process improvement. Companies use data analytics and research to optimize supply chains, target customers, and reduce risks. In the modern economy, intangible assets like intellectual property and brand reputation also derive from valuable information.

- Time

Time, though often overlooked, is a vital factor of production. It affects productivity, cost-efficiency, and market responsiveness. Timely decision-making, project execution, and delivery influence customer satisfaction and profitability. Time also determines the depreciation of assets and the lifecycle of products. Efficient time management leads to leaner operations and better resource utilization. In fast-moving markets, the ability to act quickly on opportunities is a decisive competitive advantage.

- Technology

Technology enhances all other factors of production by increasing efficiency, reducing costs, and enabling innovation. It transforms traditional processes into automated, scalable, and intelligent systems. For instance, AI, robotics, and cloud computing streamline manufacturing, logistics, and customer service. Technology reduces reliance on physical labor and optimizes capital usage. In modern business strategy, adopting and upgrading technology is not optional—it is essential for survival, growth, and staying ahead in competitive markets.

Production Function:

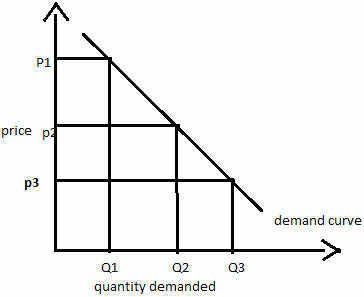

Production Function is an economic concept that describes the relationship between the inputs used in production and the resulting output. It shows how different combinations of labor, capital, and other factors of production contribute to the production of goods or services. The production function helps in understanding the efficiency of resource utilization, and how changes in the quantity of inputs affect the level of output. It is often expressed as an equation or graph, representing the technological relationship in production.

Mathematically, such a basic relationship between inputs and outputs may be expressed as:

Q = f( L, C, N )

Where

Q = Quantity of output

L = Labour

C = Capital

N = Land.

Hence, the level of output (Q), depends on the quantities of different inputs (L, C, N) available to the firm. In the simplest case, where there are only two inputs, labour (L) and capital (C) and one output (Q), the production function becomes.

Q = f(L, C)

“The production function is a technical or engineering relation between input and output. As long as the natural laws of technology remain unchanged, the production function remains unchanged.” Prof. L.R. Klein

“Production function is the relationship between inputs of productive services per unit of time and outputs of product per unit of time.” Prof. George J. Stigler

“The relationship between inputs and outputs is summarized in what is called the production function. This is a technological relation showing for a given state of technological knowledge how much can be produced with given amounts of inputs.” Prof. Richard J. Lipsey

Thus, from the above definitions, we can conclude that production function shows for a given state of technological knowledge, the relation between physical quantities of inputs and outputs achieved per period of time.

Features of Production Function:

Following are the main features of production function:

1. Substitutability

The factors of production or inputs are substitutes of one another which make it possible to vary the total output by changing the quantity of one or a few inputs, while the quantities of all other inputs are held constant. It is the substitutability of the factors of production that gives rise to the laws of variable proportions.

2. Complementarity

The factors of production are also complementary to one another, that is, the two or more inputs are to be used together as nothing will be produced if the quantity of either of the inputs used in the production process is zero.

The principles of returns to scale is another manifestation of complementarity of inputs as it reveals that the quantity of all inputs are to be increased simultaneously in order to attain a higher scale of total output.

3. Specificity

It reveals that the inputs are specific to the production of a particular product. Machines and equipment’s, specialized workers and raw materials are a few examples of the specificity of factors of production. The specificity may not be complete as factors may be used for production of other commodities too. This reveals that in the production process none of the factors can be ignored and in some cases ignorance to even slightest extent is not possible if the factors are perfectly specific.

Production involves time; hence, the way the inputs are combined is determined to a large extent by the time period under consideration. The greater the time period, the greater the freedom the producer has to vary the quantities of various inputs used in the production process.

In the production function, variation in total output by varying the quantities of all inputs is possible only in the long run whereas the variation in total output by varying the quantity of single input may be possible even in the short run.

Time Period and Production Functions

The production function is differently defined in the short run and in the long run. This distinction is extremely relevant in microeconomics. The distinction is based on the nature of factor inputs.

Those inputs that vary directly with the output are called variable factors. These are the factors that can be changed. Variable factors exist in both, the short run and the long run. Examples of variable factors include daily-wage labour, raw materials, etc.

On the other hand, those factors that cannot be varied or changed as the output changes are called fixed factors. These factors are normally characteristic of the short run or short period of time only. Fixed factors do not exist in the long run.

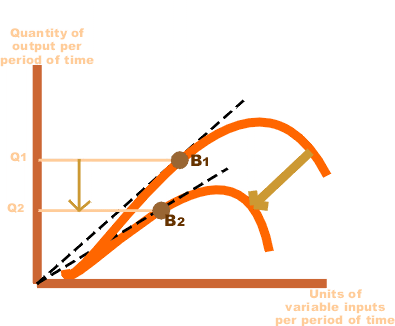

Consequently, we can define two production functions: short-run and long-run. The short-run production function defines the relationship between one variable factor (keeping all other factors fixed) and the output. The law of returns to a factor explains such a production function.

For example, consider that a firm has 20 units of labour and 6 acres of land and it initially uses one unit of labour only (variable factor) on its land (fixed factor). So, the land-labour ratio is 6:1. Now, if the firm chooses to employ 2 units of labour, then the land-labour ratio becomes 3:1 (6:2).

The long-run production function is different in concept from the short run production function. Here, all factors are varied in the same proportion. The law that is used to explain this is called the law of returns to scale. It measures by how much proportion the output changes when inputs are changed proportionately.

Types of Production Function:

1. Short-Run Production Function

In the short run, at least one input is fixed (usually capital), while other inputs (like labor) are variable. The short-run production function examines how changes in variable inputs affect output, keeping the fixed input constant.

Key Features:

- Focuses on the law of variable proportions (diminishing marginal returns).

- Output increases initially at an increasing rate, then at a decreasing rate, and eventually may decline.

Example:

A factory with fixed machinery (capital) adds more workers (labor). Initially, productivity increases, but as workers crowd the factory, additional output diminishes.

2. Long-Run Production Function

In the long run, all inputs are variable, allowing firms to adjust labor, capital, and other resources fully. The long-run production function focuses on the optimal combination of inputs to achieve maximum efficiency and output.

Key Features:

- Examines returns to scale:

- Increasing Returns to Scale: Doubling inputs results in more than double the output.

- Constant Returns to Scale: Doubling inputs results in a proportional doubling of output.

- Decreasing Returns to Scale: Doubling inputs results in less than double the output.

- Useful for long-term planning and investment decisions.

3. Cobb-Douglas Production Function

A mathematical representation of the relationship between two or more inputs (e.g., labor and capital) and output. It is commonly expressed as:

Q = A*L^α*K^β*

Where:

- Q: Total output

- L: Labor input

- K: Capital input

- α,β: Elasticities of output with respect to labor and capital

- A: Total factor productivity

Key Features:

- Demonstrates the contribution of labor and capital to output.

- Widely used in economics for empirical studies and forecasting.

4. Fixed Proportions Production Function (Leontief Production Function)

In this type, inputs are used in fixed proportions to produce output. Increasing one input without proportionately increasing the other does not lead to higher output.

Example:

A car requires one engine and four tires. Adding more engines without increasing the number of tires will not produce more cars.

5. Variable Proportions Production Function

Inputs can be substituted for one another in varying proportions while producing the same level of output.

Example:

A firm can use either more machines and less labor or more labor and fewer machines to produce the same output.

6. Isoquant Production Function

An isoquant represents all possible combinations of two inputs (e.g., labor and capital) that produce the same level of output. The isoquant approach analyzes how inputs can be substituted while maintaining output levels.

Key Features:

- Focuses on input substitution.

- Helps determine the least-cost combination of inputs for a given output.