Relevant information & Decision making

Managerial decision making is a process of making choices. If a choice is to be made among alternatives, there must be differences among the alternatives. Relevant information should be used by the decision maker in evaluating the alternatives and in making decisions.

Characteristics of Relevant Information:

Relevant information has two characteristics:

- Impact on the Future:

Relevant information has bearing on the future. Relevant information focuses on the future because every decision deals with selecting courses of action for the future. Nothing can be done to alter the past. The consequences of decisions are born in the future, not the past. Information to be relevant (i.e. relevant costs and benefits) to a decision should imply a future event.

Since relevant information involves future events, the managerial accountant must predict the amounts of the relevant costs and benefits. In making these predictions, the accountant often will use estimates of cost behavior based on historical data. There is an important and subtle issue here. Relevant information must involve costs and benefits to be realized in the future. However, the accountant’s predictions of those costs and benefits often are based on data from the past.

- Different under Different Alternatives:

Relevant information includes costs and benefits that differ among the alternatives. Expected future revenues and costs that do not differ or remain the same across alternatives have no impact on the decision and therefore irrelevant and should be eliminated from the relevant information analysis.

Further, in relevant information, due weight-age must be given to qualitative factors and quantitative non financial factors.

According to Hilton, information to be useful for decision making should possess three characteristics:

- Relevance

- Accuracy

- Timeliness

Relevant Information and Differential Analysis:

Relevant information implies relevant costs and relevant revenues (benefits) which are useful to evaluate alternatives, to ascertain the effect of various alternatives on profit and to finally select the alternative with the greatest benefit.

Relevant revenues and relevant costs are defined as the current and future values that differ among the alternatives under consideration. They are the differences between the alternatives under consideration. The amounts of such differences are called differentials and the (accounting) analysis concerned with the effect of alternatives on revenues and costs is called differential analysis.

Thus, differential analysis, known as relevant information analysis also, is defined as the use of relevant revenues and relevant costs in decision making. Relevant revenues and costs are also known as differential revenues and differential costs. This analysis provides a decision rule to managers in decision-making which is ‘the alternative that gives the greatest incremental profit should be selected’. Incremental profit is the difference between the relevant revenues and relevant costs of each alternative.

A differential analysis of relevant costs is always preferable to complete analysis of all costs and revenues for a number of reasons:

(i) A differential analysis focuses on only those items that differ, providing a clearer picture of the impact of the decision at hand. Management is less apt to be confused by this analysis than by one that combines relevant and irrelevant items.

(ii) A differential analysis contains fewer items, making it easier and quicker to prepare.

(iii) A differential analysis can help to simplify complex situations (such as those encountered by multiple-product or multiple-plant firms), when it is difficult to develop complete firm-wide statements to analyze all decision alternatives.

Relevant Revenues:

Relevant (differential) revenue as stated earlier, is the amount of increase or decrease in revenue expected from a particular course of action as compared with an alternative. For instance, assume that a plant is being used to manufacture product A, which gives revenue of Rs 3, 00,000. If the plant could be used to make product B, which will provide revenue of Rs 3,50,000 the differential revenue from making and selling product B will be Rs 50,000.

Accrual Profit and Cash Flow:

Relevant revenues are like cash inflows. If the amount of accrual profit and cash flow differs, the manager should give importance to cash flow. I or short-run managerial decisions, timing of cash flow, i.e., when the cash flows are received, are not so important. However, for long-run decisions where the time span is usually for more than one year, the timing of cash flows is important in the evaluation of alternatives and in making decisions.

Relevant Costs:

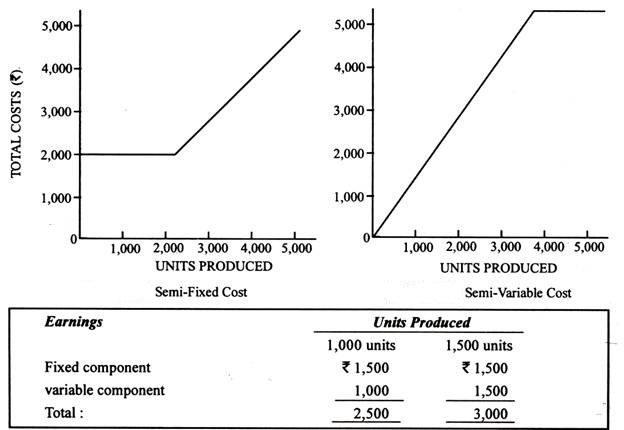

Relevant Costs are also known as differential costs, decision making costs. Relevant or differential cost is the difference in the total costs between alternative choices. It is difference in total costs between two volumes. It is the cost that should be considered when a decision is made involving an increase or decrease of n units of output above a specified output.

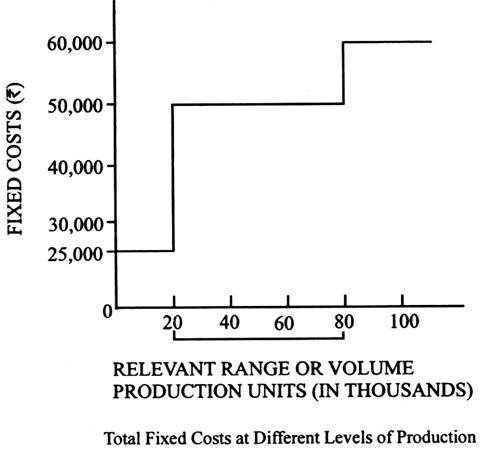

When a decision results in an increased cost, the differential cost may be referred to as an incremental cost. If the cost decreases, the differential cost may be referred to as a decremental cost. The incremental cost includes the change in fixed component as well as the variable component. Assume that a company has physical facilities to manufacture 20,000 units of a product; production beyond that point would require the installation of additional equipment, that is, fixed costs as well as variable costs will have to be incurred if management desires to produce more than 20,000 units.

Differential and Incremental:

The term differential is more inclusive than incremental. The latter term suggests increases, and some decisions produce decreases in both revenues and costs. But the terms are not as important as what they denote. Differential costs are avoidable costs. If a company can change a cost by taking one action as opposed to another, the cost is avoidable and therefore differential.

Suppose a company could save Rs 5, 00,000 in salaries and other fixed costs if it stopped selling a product in a particular geographical region. The Rs 5, 00,000 is avoidable (differential) because it will be incurred if the company continues to sell in the region and will not be incurred if the firm stops selling in that region. Of course, the company will lose revenue if it discontinues sales in the region. Hence, the lost revenue is also differential in a decision to stop selling in the region.

Relevant costs vary with the type of decision. However, the following are the common characteristics of relevant costs:

(1) Relevant costs are expected future costs.

(2) They differ between different decision alternatives.

Expected future costs imply that the costs are expected to occur during the time period covered by the decision. For example, new product will need the incurrence of direct material, direct labour and other costs. Relevant costs also differ between decision alternatives. For example, a graduate may choose between higher education and immediate employment.

The costs that are relevant in this decision and which differ between the two decision are the costs of books, fees, etc., because these costs will not be incurred if the graduate takes up employment. However, irrelevant costs are costs of accommodation, clothing’s, etc. which will have to be incurred under both the decisions.

The differential cost concept is one of the most useful in planning and decision making. It provides a tool for testing the profitability of increased output for an acceptable alternative. In many short-run decisions, only costs, not revenues, will change. In this case, the most beneficial (profitable) decision will be one with the lowest cost because the lowest cost alternative will give the highest profit for the business enterprise, provided all other factors remain constant.