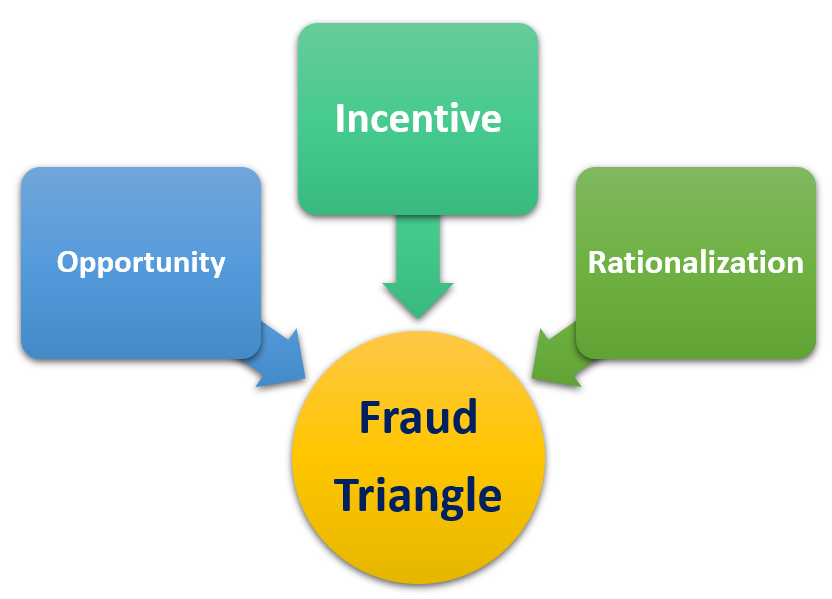

Fraud Triangle

he fraud triangle is a framework commonly used in auditing to explain the reason behind an individual’s decision to commit fraud. The fraud triangle outlines three components that contribute to increasing the risk of fraud:

(1) Opportunity

(2) Incentive

(3) Rationalization

Opportunity

Opportunity refers to circumstances that allow fraud to occur. In the fraud triangle, it is the only component that a company exercises complete control over. Examples that provide opportunities for committing fraud include:

Poor tone at the top

Tone at the top refers to upper management and the board of directors’ commitment to being ethical, showing integrity, and being honest a poor tone at the top results in a company that is more susceptible to fraud.

Weak internal controls

Internal controls are processes and procedures implemented to ensure the integrity of accounting and financial information. Weak internal controls such as poor separation of duties, lack of supervision, and poor documentation of processes give rise to opportunities for fraud.

Inadequate accounting policies

Accounting policies refer to how items on the financial statements are recorded. Poor (inadequate) accounting policies may provide an opportunity for employees to manipulate numbers.

Incentive

Incentive, alternatively called pressure, refers to an employee’s mindset towards committing fraud. Examples of things that provide incentives for committing fraud include:

Investor and analyst expectations

The need to meet or exceed investor and analyst expectations to ensure stock prices are maintained or increased can create pressure to commit fraud.

Bonuses based on a financial metric

Common financial metrics used to assess the performance of an employee are revenues and net income. Bonuses that are based on a financial metric create pressure for employees to meet targets, which, in turn, may cause them to commit fraud to achieve the objective.

Personal incentives

Personal incentives may include wanting to earn more money, the need to pay personal bills, a gambling addiction, etc.

Rationalization

Rationalization refers to an individual’s justification for committing fraud. Examples of common rationalizations that fraud committers use include:

“Upper management is doing it as well”

A poor tone at the top may cause an individual to follow in the footsteps of those higher in the corporate hierarchy.

“They treated me wrong”

An individual may be spiteful towards their manager or employer and believe that committing fraud is a way of getting payback.

“There is no other solution”

An individual may believe that they might lose everything (for example, losing a job) unless they commit fraud.

Step 1: The pressure on the individual: The motivation behind the crime and can be either personal financial pressure, such as debt problems, or workplace debt problems, such as a shortfall in revenue. The pressure is seen by the individual as unsolvable by orthodox, legal, sanctioned routes and unshareable with others who may be able to offer assistance. A common example of a perceived unshareable financial problem is gambling debt. Maintenance of a lifestyle is another common example.

Step 2: The opportunity to commit fraud: The means by which the individual will defraud the organisation. In this stage the worker sees a clear course of action by which they can abuse their position to solve the perceived unshareable financial problem in a way that again, perceived by them is unlikely to be discovered. In many cases the ability to solve the problem in secret is key to the perception of a viable opportunity.

Step 3: The ability rationalises the crime: The final stage in the fraud triangle. This is a cognitive stage and requires the fraudster to be able to justify the crime in a way that is acceptable to his or her internal moral compass. Most fraudsters are first-time criminals and do not see themselves as criminals, but rather a victim of circumstance. Rationalisations are often based on external factors, such as a need to take care of a family, or a dishonest employer which is seen to minimise or mitigate the harm done by the crime.