The term profit has distinct meaning for different people, such as businessmen, accountants, policymakers, workers and economists. Profit simply means a positive gain generated from business operations or investment after subtracting all expenses or costs.

In economic terms profit is defined as a reward received by an entrepreneur by combining all the factors of production to serve the need of individuals in the economy faced with uncertainties. In a layman language, profit refers to an income that flow to investor. In accountancy, profit implies excess of revenue over all paid-out costs. Profit in economics is termed as a pure profit or economic profit or just profit.

Profit differs from the return in three respects namely:

- Profit is a residual income, while return is total revenue.

- Profits may be negative, whereas returns, such as wages and interest are always positive.

- Profits have greater fluctuations than returns.

- Risk-Bearing Theory of Profit:

The main proponent of this theory is Prof. Hawley. According to Hawley, one of the major functions of an entrepreneur is to bear risk that is associated first with the setting up of the business and then with the management of the business.

The risks in a business are of two types:

(i) Risk involved in the selection of the field of business; and

(ii) Risk associated with the management of the business.

After investing capital in a particular business, the entrepreneur has to wait for a long time before he can know if his selection of the field of business has been appropriate this long wait is a form of risk-bearing.

Again, while managing the business, the entrepreneur has to bear all the risks arising out of unexpected changes in the demand and supply for the product.

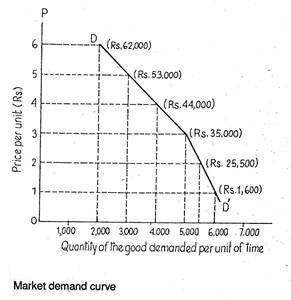

There may be sudden changes in the demand for a good owing to changes in the tastes, habits and incomes of the buyers, changes in the availability and prices of the substitute products, etc.

Also, there may be unexpected changes in the supply of the good owing to changes in the availability of the factors of production and changes in production techniques, etc.

Therefore, that the entrepreneur has to bear the risks associated with the unexpected changes in demand and supply of the product and also the risks associated with the consequent changes in the price of the product, total revenue and profit of the firm. The greater the ability of the entrepreneur to bear all these risks, the higher would be his level of profit. This is the main contention of the risk-bearing theory.

Critical Evaluation of the Theory:

The arguments that may be advanced in favour of the theory are:

(i) The theory attracts our attention to the fact that one of the main functions of the entrepreneurs is to bear the risks.

(ii) The theory focuses also on the fact that a very few persons come forward to play the role of entrepreneurs because here they would have to bear the risks. That is why the supply of entrepreneurial services is very limited.

Arguments Against the Theory:

Let us now come to the arguments against the theory. These are:

(i) Risk-bearing is not the only function of an entrepreneur who has to perform many vital functions. For example, the entrepreneur has to innovate at regular intervals new products, new markets and improved methods of production and business.

He may augment his revenue and reduce his expenditures through such innovations and, consequently, his profit level would go up. Therefore, profit may also be considered as a reward for effecting innovations. Again, the entrepreneurs, all of them, have not the same ability to face risks and to perform other activities.

Therefore, owing to differences in such ability, some entrepreneurs may earn rent of ability. Similarly, if the entrepreneur is able to establish a monopolistic dominance in the market, then also his income, i.e., profit, would include the added income acquired through monopoly power. Therefore, profit cannot be explained only as a reward for risk-bearing.

(ii) The entrepreneur has surely to bear risks and his profit, at least some part of it, may be considered to be a reward for risk-bearing. However, risk is a subjective concept. We cannot measure risk in an objective, cardinal manner. That is why it is not possible to establish a functional relationship between risk and profit.

(iii) The exponents of the risk-bearing theory of profit did not distinguish between insurable risk and non-insurable risk. But if we are to obtain a good estimate of the amount of risk- bearing, it is essential to remember this distinction. For, the entrepreneurs actually do not bear the burden of insurable risks, it is borne by the insurance companies.

Therefore, they cannot be considered as risks. According to Prof. Knight, the entrepreneurs bear the burden of non-insurable risks and he has called these non-insurable risks by the name of uncertainty. The entrepreneur should obtain profit as a reward for bearing this uncertainty.

- Uncertainty-Bearing Theory of Profit:

Prof. F. H. Knight (1885-1973) has developed the uncertainty-bearing theory of profit. He says that we may distinguish between insurable risks and non-insurable risks. This distinction is important. For, the entrepreneurs actually do not bear the burden of insurable risks it is borne by the insurance companies. Therefore, they cannot be considered as risks for the entrepreneurs.

For example, we know from experience that factory premises are exposed to the risk of fire. We also know why there may be fire in a factory premise, and so, we may adopt necessary measures for prevention of fire.

In spite of all this, there remains the risk of fire, and, once the insurance companies agree to bear this risk, it no longer remains a risk. In other words, according to Knight, insurable risks should not be considered as risks and there is no question of the entrepreneurs bearing this risk.

However, the entrepreneurs bear the burden of non-insurable risks for there is no insurance company to bear these risks on their behalf. Prof. Knight has called these risks the uncertainties.

He tells us that the entrepreneur should get profit as a reward for bearing the uncertainties of the business world. The more prudently an entrepreneur bears the uncertainties, the more should be the amount of profit to reward him with.

Critical Evaluation of the Theory:

The following arguments are advanced in favour of the uncertainty-bearing theory of profit:

(i) The theory attracts our attention to the fact that not all types of risk are to be borne by the entrepreneur. He actually bears the non-insurable risks. The insurable risks are taken care of by the insurance agencies.

(ii) The theory tells us that, like all other productive services, uncertainty-bearing is also a productive service. The entrepreneur supplies this productive service and profit is the price of this service.

(iii) Since, in general, people are averse to uncertainty-bearing, the supply of entrepreneurs in the real world is very small. This impression is also obtained from the theory.

Arguments Against the Theory:

The following arguments are advanced against the theory:

(i) Uncertainty-bearing is not the only function of an entrepreneur. The innovation of new products, new markets or new production and business techniques are also among the main tasks of an entrepreneur.

Therefore, along with the function of uncertainty-bearing, that of innovation may also be the source of profit. Again, the rent of ability and monopolistic dominance may also be the sources of profit. Similarly, a firm may earn profit owing to its goodwill in the market. Therefore, we cannot say that profit arises only as a reward for uncertainty-bearing.

(ii) Uncertainty is something subjective: It has no objective, cardinal measure. In the case of organisation and management of a particular business, different entrepreneurs may have different perceptions of the degree of uncertainty involved. Therefore, it is almost impossible to build up a functional relation between uncertainty and profit.

- Rent Theory of Profit:

An American economist, Francis A. Walker (1840-97), is the exponent of the rent theory of profit. Walker says that an entrepreneur acquires profit because of his ability to perform. Walker argues like this. In a certain production process, if an entrepreneur uses land, labour and capital owned by his own self, then the residual part of his revenue, after payment is made to all these factors of production, is profit.

Now, at any particular price of the product, some entrepreneurs may have this profit equal to zero. They are called the marginal entrepreneurs. Any such marginal entrepreneur can have nothing in excess of the wage, interest and rent earned by his own labour, capital and land.

Therefore, if an entrepreneur’s ability to perform is more than that of a marginal entrepreneur, then his cost of production would be smaller, and he would be able to earn a positive profit. In fact, the greater the efficiency of a particular entrepreneur than that of a marginal entrepreneur, the more would be the amount of profit earned by him.

There is some similarity between profit and rent. For, in the Ricardian theory of rent also, we have seen that rent is zero on marginal land and the less the cost of production and more the productivity on a plot of land, the more would be the rent enjoyed by its owners. Because of this similarity between profit and rent, Walker’s theory is called the rent theory of profit.

Critical Evaluation of the Theory:

Like the other theories of profit, Walker’s theory cannot satisfactorily explain as to why the firm and its entrepreneur should get profit. However, the theory attracts our attention to the similarity between profit and rent. But we should remember that rent is not the only element of profit.

Walker has argued that profit of the marginal entrepreneur is zero and the profits earned by an intra-marginal entrepreneur are all rent.

This contention of Walker may be correct if:

(i) An entrepreneur may supply his services only in his present business and he has no alternative employment to go to; and

(ii) The supply of entrepreneurial services or the number of entrepreneurs is completely fixed.

However, in the real world, we always see that the entrepreneurs can supply their services to many alternative areas and from the point of view of a particular business, supply of entrepreneurial services is not completely fixed—the supply can increase if the reward increases. Therefore, in any particular business, the minimum supply price of entrepreneurial services is not zero.

Loosely speaking, the minimum supply price of an entrepreneur in his present business would be equal to the maximum amount of reward that he may avail of in an alternative field of engagement, other things (i.e., risk or harassment factors) remaining the same. The minimum supply price of the entrepreneur’s services in his present engagement is called his normal profit.

If an entrepreneur is able to earn profits in excess of his normal profit, then this excess is a surplus and this surplus is called pure or economic profit. The amount of pure profit an entrepreneur may earn would depend upon the efficiency of his performance.

The more his efficiency, the more he would be able to earn as pure profit. Therefore, pure profit which is the excess over normal profit, is of the nature of the rent of ability. However, we have to remember here that the profit of a firm also includes what is known as windfall or chance income.

Therefore, the pure profit is a surplus which includes the rental surplus as also the surplus due to the windfall or chance factors. Therefore, pure profit is a mixed surplus.

- Innovation Theory of Profit:

The innovation theory of profit was developed by Prof. Joseph A. Schumpeter (1883-1950). According to Schumpeter, the main function of an entrepreneur is to innovate. Here we have to remember first the distinction which Schumpeter had made between invention and innovation.

Invention is the discovery of a law of nature by a scientist. On the other hand, if an entrepreneur manufactures a new product or introduces a new production technique by using the newly discovered law of nature, and thereby makes the commercial use of the invention possible, then this is called innovation.

For example, the scientists have discovered or invented the laws of science that are behind the manufacture of the goods like electric lights or fans, radio sets, television sets, refrigerators and such other goods. But the entrepreneurs have innovated these goods. Innovation is the commercial use of the laws of science that have been discovered by the scientists.

Schumpeter has said that if the entrepreneur can innovate new techniques of production and sale, if he can innovate a new product or a new model of an old product and if he can find new markets for selling the product, then Only, he will be able to play the role of a pioneer in the business world and increase the amount of profit. We may call this increase in profit the innovation-induced profit.

Criticisms of the Theory:

Schumpeter’s innovation theory of profit has explained nicely how an entrepreneur may increase the amount of profit by means of innovations. But this theory cannot fully explain why profit arises or why the entrepreneurs should earn profit.

For example, we know that an entrepreneur should obtain profit as a reward for bearing risk or uncertainty, for his ability to establish monopolistic dominance, and for many other reasons. But Schumpeter did not consider these factors that might work behind the emergence of profit.

- Dynamic Theory of Profit:

According to J. M. Clark (1884-1963), an American economist, profit can emerge only in a dynamic society. That is why his theory is called the dynamic theory of profit. We have to remember here the distinction between a dynamic society and a static society.

The society which is constantly changing and where the socio-economic factors like population and labour force, saving and investment, volume of capital, tastes and choices of the people, the standard of education, health and culture, etc. are always changing, is called a dynamic society.

On the other hand, the society where these changes do not occur, is called a static society. According to Clark, changes do not occur in a static society. That is why here there is no risk or uncertainty. In such a society, everything goes on according to routine and everyone has a prior information of what will happen and when.

So here the entrepreneur bears no uncertainty while organising a production process, and he should not get profit as a reward. Therefore, Clark concludes that profit does not arise in a static society. The entrepreneur obtains a price for his product in this society, which would just cover only his cost (including normal profit).

The dynamic society, on the other hand, goes through changes. There the tastes, habits and fashion, the availability of factors of production and the methods and techniques of production are all changing. That is why, in such a society, the entrepreneur has to bear uncertainty. The more successful he is in managing the uncertainties, the higher would be the profit level acquired by him.

It is clear in the above analysis that in a dynamic society, the entrepreneur has to be innovative, for innovations lead to changes and changes inspire innovations. On the other hand, in a static society, innovations do not occur, for such a society does not experience changes. That is why the dynamic theory of profit is considered to be a more general form of Schumpeter’s innovation theory.

Critical Estimates:

The dynamic theory attracts our attention to the fact that dynamism is urgently necessary for the social and economic progress of a society. If the society is dynamic, the entrepreneurs would earn profit and, if they can earn profit, the supply of entrepreneurship increases and, consequently, production in the society increases.

But the dynamic theory of profit also is not a complete theory. Because, this theory also does not explain all the causes of the emergence of profit. For example, this theory does not mention that profit may also arise because of the monopoly power of the firm.

- Monopoly Power Theory of Profit:

Many economists think that if there is perfect competition in the markets, there cannot be any profit, because absence of competition creates opportunities in the markets to acquire profit. As we know, under perfect competition, the buyers and sellers are assumed to possess full knowledge about the conditions prevailing in the markets.

That is why if the firms in an industry happen to earn more than normal profit in the short run, then in the long run, number of firms and the supply of the product would be increasing and the price of the product would be decreasing till all the existing firms would earn just the amount of normal profit. A firm under perfect competition is one of a large number of firms.

That is why it can sell more or less any amount of its product at the market-determined price. The entrepreneur, here, is not required to take an individual initiative to increase the demand for his product and his sales. Therefore, here the entrepreneur performs his routine activities and for this he gets no more than the normal profit.

On the other hand, if the entrepreneur possesses monopoly power in the market, then he would have to exert individual initiative in giving leadership in the market. Now, in order to maintain his monopoly power and to increase this power, he would have to exercise necessary efforts.

The entrepreneur here has to bear risk and uncertainty, and he would have to expand the dominance of his firm in the market through innovations. If the entrepreneur can perform his job successfully, then he can increase the demand for his product and get a higher price. Consequently, the amount of pure profit earned by him may increase.

Criticisms:

We may argue in favour of this theory that it has rightly emphasised the role of monopoly power in the emergence of profit. But this also cannot be a complete theory of profit.

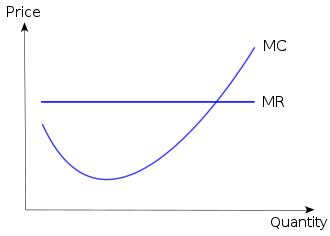

For we know that even a monopolistic firm can earn less than normal profit or negative pure profit, i.e., we may have p < AC at his MR = MC point. Therefore, the existence of monopoly elements in the market may be a necessary condition for the emergence of profit but it is not a sufficient condition.

- Labour Exploitation Theory of Profit:

According to the great philosopher and classical economist, Karl Marx (1818-1883), labour is the only factor of production which can produce surplus value. The capitalists acquire profit by expropriating this surplus value. Marx has said that labour is the only productive factor.

Labour is given a rate of wage which is much smaller than the net value produced by it with the help of machines, raw materials, etc. The surplus value is defined as the difference between the net value produced by labour and what it actually gets as wage.

This surplus value is the profit of the entrepreneur who represents the capitalists. There would be an increase in the productivity of labour when this profit is converted into capital and invested again, for now the labour would be able to use more of capital goods or machines.

As the productivity of labour increases, the surplus value created by labour also increases for the rate of wage of the workers generally does not increase, or, increases at a much smaller rate. Thus exploitation of labour goes on increasing at an increasing rate and, along with it, the stock of capital also increases.

Criticisms:

In the labour exploitation theory of profit, the role of labour in the creation of surplus value and the subject of labour exploitation have been rightly emphasised. However, many economists think that, like labour, the other factors of production, like land and capital, are also productive.

Besides, Marx has said that it is the capitalists that acquire profit, i.e., he thinks that capitalists are identical with entrepreneurs, although, in modern economic system, entrepreneurs and capitalists may be separate persons.

Lastly, Marx does not consider the fact that sometimes the entrepreneurs may have to bear risks and uncertainties. Therefore, Marx’s theory, too, cannot be considered to be a complete theory of profit.

- Marginal Productivity Theory of Profit:

We already know how the marginal productivity (MP) theory of factor pricing may be applied to the determination of the rates of wage and interest. We shall now see how far the theory is relevant in determining the rate of profit. The MP theory says that the price of a factor would be equal to the value of its marginal product (VMP).

Therefore, according to the MP theory, the rate of profit would be equal to the VMP of entrepreneurship or entrepreneurial services. According to definition, the MP of entrepreneurship is the increment in total output obtained as a result of use of the marginal unit of entrepreneurial services.

It may be noted here that if we talk of one marginal unit of entrepreneur in place of one marginal unit of entrepreneurial services, then there would be confusion since a business firm may have one, or, at best, a few entrepreneurs, and entrepreneur is not a continuous variable.

Therefore, while examining the relevance of the MP theory in the area of profit, we should talk not of entrepreneurs, but of entrepreneurial services, the quantity used of which may be measured, say, in units of time as quantity used of labour is expressed in hours.

Then we would be able to say: if the VMP of entrepreneurial services is greater than the rate of profit determined in the market, then the entrepreneur would go on increasing the amount of entrepreneurial services used till the VMP of these services diminishes owing to the law of diminishing returns, to become equal to the rate of profit.

Like this:

Like Loading...