In an economic model, agents have a comparative advantage over others in producing a particular good if they can produce that good at a lower relative opportunity cost or autarky price, i.e. at a lower relative marginal cost prior to trade. Comparative advantage describes the economic reality of the work gains from trade for individuals, firms, or nations, which arise from differences in their factor endowments or technological progress. (One should not compare the monetary costs of production or even the resource costs (labor needed per unit of output) of production. Instead, one must compare the opportunity costs of producing goods across countries.

David Ricardo believed that the international trade is governed by the comparative cost advantage rather than the absolute cost advantage. A country will specialise in that line of production in which it has a greater relative or comparative advantage in costs than other countries and will depend upon imports from abroad of all such commodities in which it has relative cost disadvantage.

Suppose India produces computers and rice at a high cost while Japan produces both the commodities at a low cost. It does not mean that Japan will specialise in both rice and computers and India will have nothing to export. If Japan can produce rice at a relatively lesser cost than computers, it will decide to specialise in the production and export of computers and India, which has less comparative cost disadvantage in the production of rice than computers will decide to specialise in the production of rice and export it to Japan in exchange of computers.

David Ricardo developed the classical theory of comparative advantage in 1817 to explain why countries engage in international trade even when one country’s workers are more efficient at producing every single good than workers in other countries. He demonstrated that if two countries capable of producing two commodities engage in the free market, then each country will increase its overall consumption by exporting the good for which it has a comparative advantage while importing the other good, provided that there exist differences in labor productivity between both countries. Widely regarded as one of the most powerful yet counter-intuitive insights in economics, Ricardo’s theory implies that comparative advantage rather than absolute advantage is responsible for much of international trade.

Assumption’s

(i) There is no intervention by the government in economic system.

(ii) Perfect competition exists both in the commodity and factor markets.

(iii) There are static conditions in the economy. It implies that factors supplies, techniques of production and tastes and preferences are given and constant.

(iv) Production function is homogeneous of the first degree. It implies that output changes exactly in the same ratio in which the factor inputs are varied. In other words, production is governed by constant returns to scale.

(v) Labour is the only factor of production and the cost of producing a commodity is expressed in labour units.

(vi) Labour is perfectly mobile within the country but perfectly immobile among different countries.

(vii) Transport costs are absent so that production cost, measured in terms of labour input alone, determines the cost of producing a given commodity.

(viii) There are only two commodities to be exchanged between the two countries.

(ix) Money is non-existent and prices of different goods are measured by their real cost of production.

(x) There is full employment of resources in both the countries.

(xi) Trade between two countries takes place on the basis of barter.

Two-commodity model can be analysed through the Table.

|

Table Labour cost of Production |

||

|

Country |

Labour cost per unit of commodity in Man-Hours | |

| Commodity X | Commodity Y | |

|

A |

12 |

10 |

| B | 16 |

12 |

The Table indicates that country A has an absolute advantage in producing both the commodities through smaller inputs of labour than in country B. In relative terms, however, country A has comparative advantage in specialising in the production and export of commodity X while country B will specialise in the production and export of commodity Y.

In country A, domestic exchange ratio between X and Y is 12 : 10, i.e., 1 unit of X = 12/10 or 1.20 units of Y. Alternatively, 1 unit of Y= 10/12 or 0.83 units of X.

In country B, the domestic exchange ratio is 16 : 12, i.e., 1 unit of X = 16/12 or 1.33 units of Y. Alternatively, 1 unit of Y = 16/12 or 0.75 unit of X.

From the above cost ratios, it follows that country A has comparative cost advantage in the production of X and B has comparatively lesser cost disadvantage in the production of Y.

In algebraic terms, let labour cost of producing X-commodity in country A is a1 and in country B is a2. The labour cost of producing Y-commodity in countries A and B are respectively a3 and a4.

The absolute differences in costs can be measured as:

a1/a2 < 1 < a3/a4

It shows that country A has absolute advantage in producing X and country B has an absolute advantage in commodity Y.

The comparative differences in costs can be measured as:

a1/a2 < a3/a4 < 1

The Table satisfies the condition specified for comparative difference in costs;

a1/a2 < 1 < a3/a4 < 1

12/16 < 10/12 < 1

In case a1/a2 = a3/a4, there are equal differences in costs and there is no possibility of trade between the two countries.

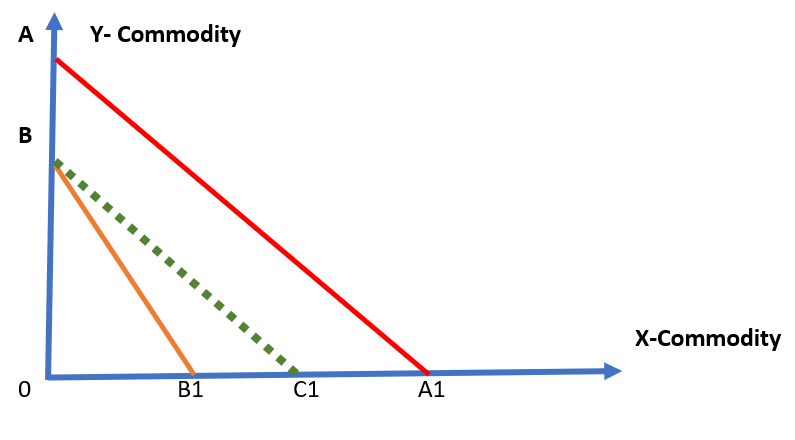

In Fig. 2.2, AA1 and BB1 are the production possibility curves pertaining to countries A and B. Given the same number of productive resources, A can produce larger quantities of both the commodities than the country B. It means country A has absolute cost advantage over B in respect of both the commodities.

If the curve BC1 is drawn parallel to AA1; the curve BC1 can represent the production possibility curve of country A. If country A gives up OB quantity of Y and diverts resources to the production of X, it can produce OC1 quantity of X, which is more than OB1. It means the country A has comparative cost advantage in the production of X-commodity.

From the point of view of B, it can produce the same quantity OB of Y, if it gives up the production of smaller quantity OB1 of X. If signifies that country B has less comparative disadvantage in the production of Y commodity. Accordingly, country A will specialise in the production and export of X commodity, while country B will specialise in the production and export of Y-commodity.

Gain from Trade:

The comparative cost principle underlines the fact that two countries will stand to gain through trade so long as the cost ratios for two countries are not equal. On the basis of Table , country A specialises in the production of X commodity, while country B specialises in the production of Y commodity.

In the absence of international trade, the domestic exchange ratio between X and Y commodities in these two countries are:

Country A: 1 unit of X = 12/10 or 1-20 units of Y

Country B: 1 unit of Y = 12/16 or 0-75 unit of X

If trade takes place and two countries agree to exchange 1 unit of X for 1 unit of Y, the gain from trade for country A amounts to 0.20 units of Y for each unit of X. In case of country B, the gain from trade amounts to 0.25 unit of X for each unit of Y. Thus the comparative costs principle confers gain upon both the countries.

One thought on “Ricardo’s Theory of Comparative cost advantage, Gain from Trade”