HRM can be seen as part of the wider and longer debate about the nature of management in general and the management of employees in particular. This means that tracing the antecedents of HRM is as elusive an exercise as arriving at its defining characteristics. Certainly there are antecedents in organizational theory, and particularly that of the human relations school, but the nature of HRM has involved important elements of strategic management and business policy, coupled with operations management, which make a simple ‘family tree’ explanation of HRM’s derivation highly improbable.

What can be said is that the origins of HRM lie within employment practices associated with welfare capitalist employers in the United States during the 1930s. Both Jacoby (1997) and Foulkes (1980) argue that this type of employer exhibited an ideological opposition to unionisation and collective relations. As an alternative, welfare capitalists believed the firm, rather than third-party institutions such as the state or trade unions, should provide for the security and welfare of workers. To deter any propensity to unionise, especially once President Roosevelt’s New Deal programme commenced after 1933, welfare capitalists often paid efficiency wages, introduced health care coverage, pension plans and provided lay-off pay.

Equally, they conducted regular surveys of employee opinion and sought to secure employee commitment via the promotion of strong centralised corporate cultures and long-term cum permanent employment. Welfare capitalists pioneered individual performance-related pay, profit-sharing schemes and what is now termed teamworking. This model of employment regulation had a pioneering role in the development in what is now termed HRM but rested on structural features such as stable product markets and the absence of marked business cycles. While the presence of HRM was well established in the American business system before the 1980s, it was only after that period that HRM gained external recognition by academics and practitioners.

There are a number of reasons for its emergence since then, among the most important of which are the major pressures experienced in product markets during the recession of 1980–82, combined with a growing recognition in the USA that trade union influence in collective employment was reaching fewer employees. By the 1980s the US economy was being challenged by overseas competitors, most particularly Japan. Discussion tended to focus on two issues: ‘the productivity of the American worker’, particularly compared with the Japanese worker, ‘and the declining rate of innovation in American industries’ (Devanna et al., 1984: 33).

From this sprang a desire to create a work situation free from conflict, in which both employers and employees worked in unity towards the same goal the success of the organisation (Fombrun, 1984: 17). Beyond these prescriptive arguments and as a wide-ranging critique of institutional approaches to industrial relations analysis, Kaufman (1993) suggests that a preoccupation with pluralist industrial relations within and beyond the period of the New Deal excluded the non-union sector of the US economy for many years.

In summary, welfare capitalist employers (soft HRM) and antiunion employers (hard HRM) are embedded features within the US business system, whereas the New Deal Model was a contingent response to economic crisis in the 1930s. n the UK in the 1980s the business climate also became conducive to changes in the employment relationship. As in the USA, this was partly driven by economic pressure in the form of increased product market competition, the recession in the early part of the decade and the introduction of new technology.

However, a very significant factor in the UK, generally absent from the USA, was the desire of the government to reform and reshape the conventional model of industrial relations, which provided a rationale for the development of more employer-oriented employment policies on the part of management (Beardwell, 1992, 1996). The restructuring of the economy saw a rapid decline in the old industries and a relative rise in the service sector and in new industries based on ‘high-tech’ products and services, many of which were comparatively free from the established patterns of what was sometimes termed the ‘old’ industrial relations.

These changes were overseen by a muscular entrepreneurialism promoted by the Thatcher Conservative government in the form of privatisation and anti-union legislation ‘which encouraged firms to introduce new labour practices and to re-order their collective bargaining arrangements’ (Hendry and Pettigrew, 1990: 19).

The influence of the US ‘excellence’ literature (e.g. Peters and Waterman, 1982; Kanter, 1984) also associated the success of ‘leading edge’ companies with the motivation of employees by involved management styles that also responded to market changes. As a consequence, the concepts of employee commitment and ‘empowerment’ became another strand in the ongoing debate about management practice and HRM. A review of these issues suggests that any discussion of HRM has to come to terms with at least three fundamental problems:

- That HRM is derived from a range of antecedents, the ultimate mix of which is wholly dependent upon the stance of the analyst, and which may be drawn from an eclectic range of sources;

- That HRM is itself a contributory factor in the analysis of the employment relationship, and sets part of the context in which that debate takes place;

- That it is difficult to distinguish where the significance of HRM lies – whether it is in its supposed transformation of styles of employee management in a specific sense, or whether in a broader sense it is in its capacity to sponsor a wholly redefined relationship between management and employees that overcomes the traditional issues of control and consent at work.

This ambivalence over the definition, components and scope of HRM can be seen when examining some of the main UK and US analyses. An early model of HRM, developed by Fombrun et al. (1984), introduced the concept of strategic human resource management by which HRM policies are inextricably linked to the ‘formulation and implementation of strategic corporate and/or business objectives’. The model is illustrated in Figure(The matching model of HRM).The matching model emphasises the necessity of ‘tight fit’ between HR strategy and business strategy.

This in turn has led to a plethora of interpretations by practitioners of how these two strategies are linked. Some offer synergies between human resource planning (manpower planning) and business strategies, with the driving force rooted in the ‘product market logic’ (Evans and Lorange, 1989). Whatever the process, the result is very much an emphasis on the unitarist view of HRM: unitarism assumes that conflict or at least differing views cannot exist within the organisation because the actors – management and employees – are working to the same goal of the organisation’s success.

What makes the model particularly attractive for many personnel practitioners is the fact that HRM assumes a more important position in the formulation of organisational policies. The personnel department has often been perceived as an administrative support function with a lowly status. Personnel was now to become very much part of the human resource management of the organisation, and HRM was conceived to be more than personnel and to have peripheries wider than the normal personnel function. In order for HRM to be strategic it had to encompass all the human resource areas of the organisation and be practised by all employees.

In addition, decentralisation and devolvement of responsibility are also seen as very much part of the HRM strategy as it facilitates communication, involvement and commitment of middle management and other employees deeper within the organisation. The effectiveness of organisations thus rested on how the strategy and the structure of the organisation interrelated, a concept rooted in the view of the organisation developed by Chandler (1962) and evolved in the matching model.

The Matching Model of HRM

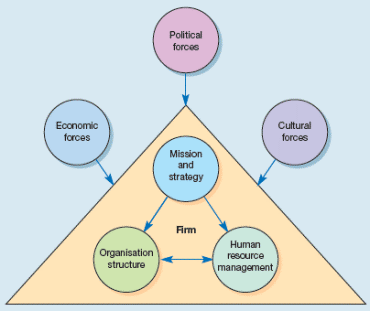

A more flexible model, illustrated in Figure, was developed by Beer et al. (1984) at Harvard University. ‘The map of HRM territory’, as the authors titled their model, recognised that there were a variety of ‘stakeholders’ in the corporation, which included shareholders, various groups of employees, the government and the community. At once the model recognises the legitimate interests of various groups, and that the creation of HRM strategies would have to recognise these interests and fuse them as much as possible into the human resource strategy and ultimately the business strategy.

This recognition of stakeholders’ interests raises a number of important questions for policy-makers in the organisation: The acknowledgement of these various interest groups has made the model much more amenable to ‘export’, as the recognition of different legal employment structures, managerial styles and cultural differences can be more easily accommodated within it.

This neopluralist model has also been recognised as being useful in the study of comparative HRM (Poole, 1990: 3–5). It is not surprising, therefore, that the Harvard model has found greater favour among academics and commentators in the UK, which has relatively strong union structures and different labour traditions from those in the United States. Nevertheless, some academics have still criticised the model as being too unitarist, while accepting its basic premise (Hendry and Pettigrew, 1990).

The Map of the HRM Territory

The first two main approaches to HRM that emerged in the UK are based on the Harvard model, which is made up of both prescriptive and analytical elements. Among the most perceptive analysts of HRM, Guest has tended to concentrate on the prescriptive components, while Pettigrew and Hendry rest on the analytical aspect (Boxall, 1992). Although using the Harvard model as a basis, both Guest and Pettigrew and Hendry have some criticisms of the model, and derive from it only that which they consider useful (Guest, 1987, 1989a, 1989b, 1990; Hendry and Pettigrew, 1986, 1990).

As we have seen, there are difficulties of definition and model-building in HRM, and this has led British interpreters to take alternative elements in building their own models. Guest is conscious that if a model is to be useful to researchers it must be useful ‘in the field’ of research, and this means that elements of HRM have to be pinned down for comparative measurement. He has therefore developed a set of propositions that he believes are amenable to testing. He also asserts that the combination of these propositions, which include strategic integration, high commitment, high quality and flexibility, creates more effective organisations (Guest, 1987).

- Strategic integration is defined as ‘the ability of organisations to integrate HRM issues into their strategic plans, to ensure that the various aspects of HRM cohere and for line managers to incorporate an HRM perspective into their decision making’.

- High commitment is defined as being ‘concerned with both behavioural commitment to pursue agreed goals and attitudinal commitment reflected in a strong identification with the enterprise’.

- High quality ‘refers to all aspects of managerial behaviour, including management of employees and investment in high-quality employees, which in turn will bear directly on the quality of the goods and services provided’.

- Finally, flexibility is seen as being ‘primarily concerned with what is sometimes called functional flexibility but also with an adaptable organisational structure with the capacity to manage innovation’.

The combination of these propositions leads to a linkage between HRM aims, policies and outcomes as shown in Table. Whether there is enough evidence to assess the relevance and efficacy of these HRM relationships will be examined later.

A Human Resource Management Framework

Hendry and Pettigrew (1990) have adapted the Harvard model by drawing on its analytical aspects. They see HRM ‘as a perspective on employment systems, characterised by their closer alignment with business strategy’. This model, illustrated in Figure, attempts a theoretically integrative framework encompassing all styles and modes of HRM and making allowances for the economic, technical and socio-political influences in society on the organisational strategy. ‘It also enables one to describe the “preconditions” governing a firm’s employment system, along with the consequences of the latter’ (Hendry and Pettigrew, 1990: 25). It thus explores ‘more fully the implications for employee relations of a variety of approaches to strategic management’ (Boxall, 1992).

Model of strategic change and human resource management

Storey studied a number of UK organisations in a series of case studies, and as a result modified still further the approaches of previous writers on HRM (Storey, 1992). Storey had previously identified two types of HRM – ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ (Storey, 1989) – the one rooted in the manpower planning approach and the other in the human relations school. He begins his approach by defining four elements that distinguish HRM:

- It is ‘human capability and commitment which, in the final analysis, distinguishes successful organisations from the rest’.

- Because HRM is of strategic importance, it needs to be considered by top management in the formulation of the corporate plan.

- ‘HRM is, therefore, seen to have long-term implications and to be integral to the core performance of the business or public sector organisation. In other words it must be the intimate concern of line managers.’

- The key levers (the deployment of human resources, evaluation of performance and the rewarding of it, etc.) ‘are to be used to seek not merely compliance but commitment’.

Storey (1992) approaches an analysis of HRM by creating an ‘ideal type’, the purpose of which ‘is to simplify by highlighting the essential features in an exaggerated way’ (p. 34). This he does by making a classificatory matrix of 27 points of difference between personnel and IR practices and HRM practices. The elements are categorised in a four-part basic outline:

- beliefs and assumptions;

- strategic concepts;

- line management;

- key levers.

This ‘ideal type’ of HRM model is not essentially an aim in itself but more a tool in enabling sets of approaches to be pinpointed in organisations for research and analytical purposes.

Twenty-seven points of difference

Storey’s theoretical model is thus based on conceptions of how organisations have been transformed from predominantly personnel/IR practices to HRM practices. As it is based on the ideal type, there are no organisations that conform to this picture in reality. It is in essence a tool for enabling comparative analysis.

One thought on “SHRM Evolution”